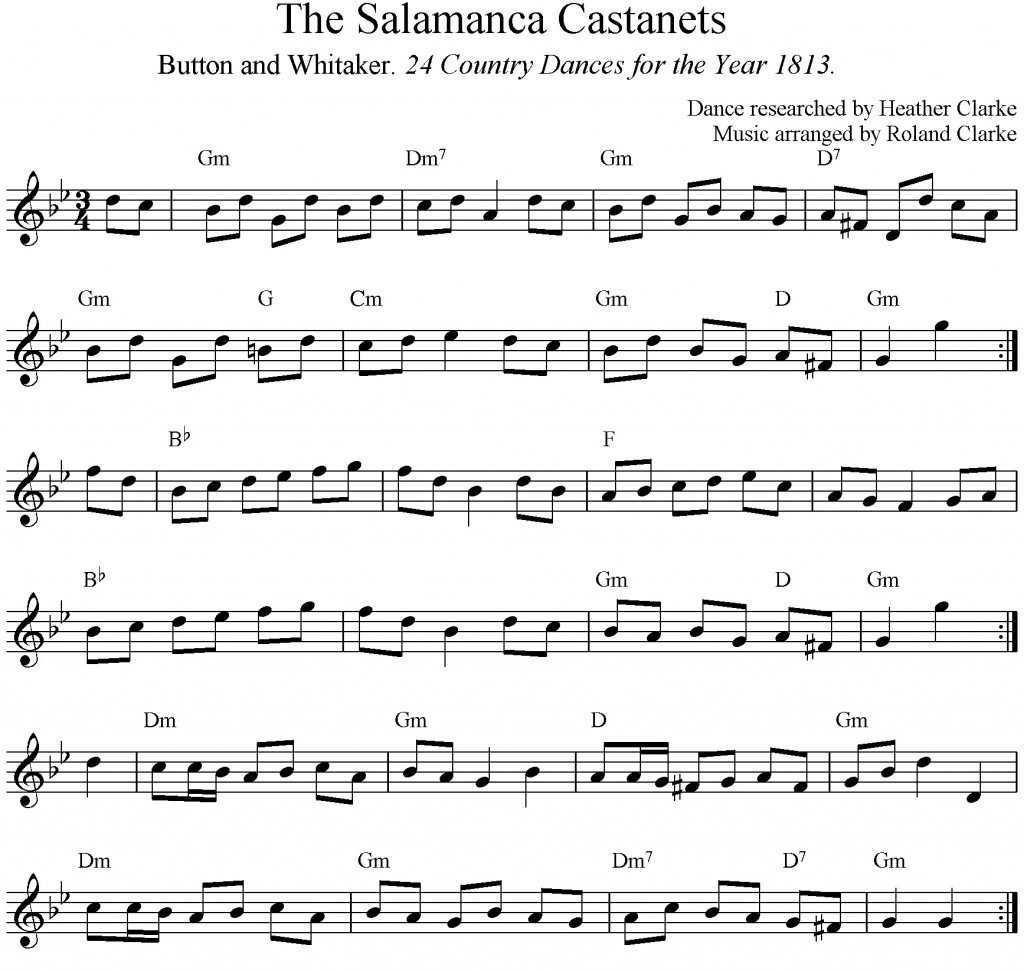

The English country dance The Salamanca Castanets was published in Button and Whittaker’s Collection of Country Dances for the Year 1813 1. It is a captivating tune, which utilises country dance figures, whilst capturing and maintaining the Spanish exuberance. Its fascinating history still resonates in Tasmania.

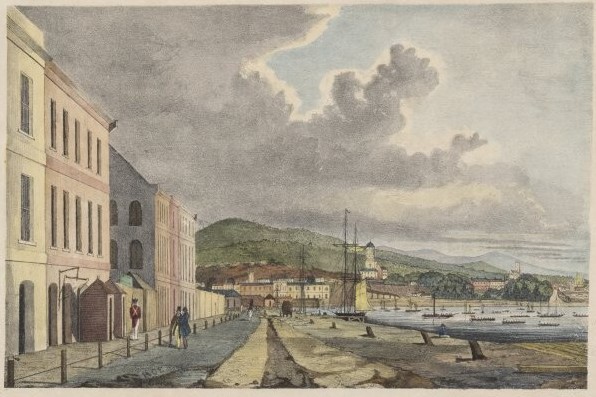

Place names in Tasmania abound with memories of the Napoleonic Wars – from Mount Wellington to Salamanca Place. Image courtesy of National Library of Australia 2

Salamanca Place is one of the best known locations in Hobart. It was named in commemoration of the Battle of Salamanca. Many early Australian settlers had participated in the campaign, lead by Wellington, to free Spain and Portugal from Napoleon’s domination. The English and Spanish alliance also generated an intriguing cultural exchange with a fusion of music and dance.

The Battle of Salamanca was fought in Spain on 22 July 1812 during the Peninsular War (1808-14). It was a pivotal confrontation which established Wellington’s reputation as a formidable commander and strategist. The battle ended with a decisive victory and was notable as one of his most impressive engagements in the campaign.

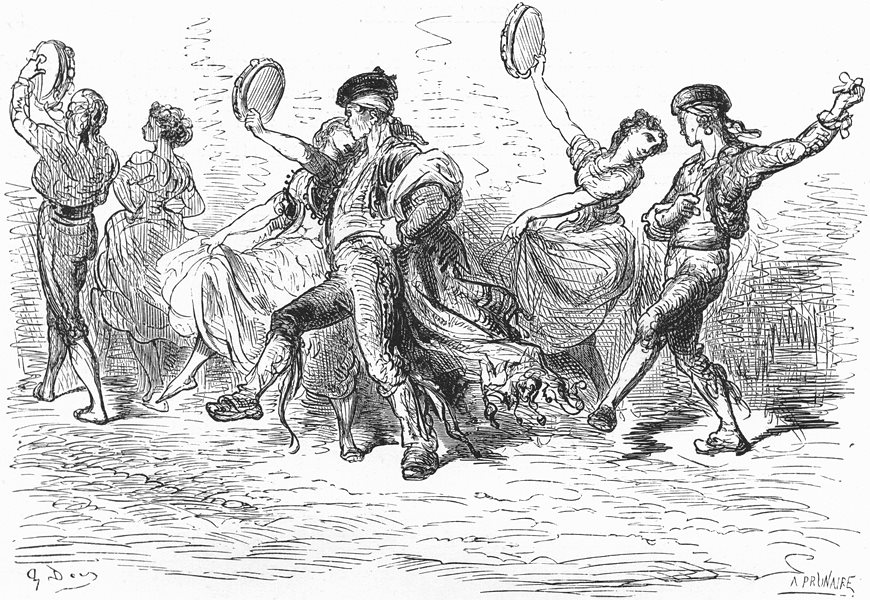

The city of Salamanca had long been a vibrant centre of historic, cultural and artistic heritage, possessing one of the oldest universities in Europe. The British troops could not have passed through the city without being awestruck by the magnificent buildings and grand public squares. However, perhaps it was the majas with their exotic dress and passionate dances who impressed the soldiers more. The majos (masc.) and majas (fem.) were the Spanish working class who retaliated against the French domination by strongly asserting their own traditional dress and customs.

Majos and Majas dancing at Fair of Rocio 4. Majo (masc.) or Maja (fem.) were terms for people from the lower classes of Spanish society, who distinguished themselves by their elaborate outfits and sense of style in dress and manners, as well as by their cheeky behaviour. 5

The costumes in Salamanca were especially flamboyant. Mordecai Noah, an American diplomat and traveller in Spain in 1813 witnessed a performance of a Spanish dance and described the elaborate dress:

Nothing can be more graceful and elegant, than their dress. The lady wears a short silk petticoat, ornamented with several flounces of lace, and rich embroidery, a tight bodice of silk, with long sleeves, the hair clubbed behind, and intertwined with artificial flowers. The actor wears a short silk jacket, kerseymere small clothes, a sash tight around his waist…every thing wears the appearance of lightness and elegance; thus accoutred, with their castanets, the dancing commences.

Noah went on to reveal the significance of the dance:

If there is anything national in Spain, it is their dances; these have been frequently explained by travellers and historians, and celebrated by poets. Every person from peer to peasant, is attached to these immemorial customs…(Noah, 1819) 6

Charles George Gray, an English officer who later settled in Australia and became a prominent figure in Queensland, wrote about his life while stationed in the Spanish city of Cadiz during the Peninsular War. He described the dances and balls which were his constant amusements:

Although partial warfare was constantly kept up between the advanced posts of the two armies, yet nothing could repress the gaiety of the people, and our leisure hours were filled up with musical parties, balls and tertulias [plays].7

The Spanish dances obviously fascinated the visitors and were eagerly imitated and modified for an English audience. Prior to the Peninsular Wars, the Spanish Fandango had become an extremely popular dance amongst the aristocracy in Spain and Europe in the mid 1700s 8. This passionate dance inspired an English country dance version, which first appeared in Thompson’s Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1774. It does not appear to demonstrate any obvious relationship to the original hot-blooded dance.

With the start of the Peninsular Wars in 1808, the attention of the English was again turned to Spain and a number of country dances reflected this interest: The Spanish Patriots (1809), Spanish Dance at Talavera (1810) in honour of the Battle of Talavera in the previous year, and The Celebrated Bollero (1810). The Salamanca Castanets was published in Button and Whitaker’s 24 Country Dances for the Year 1813, one year after the famous battle.

In 1816, perhaps inspired by these earlier dances, Edward Payne “one of the most influential Dance Masters of Regency London” 10 began advertising Waltzing, Quadrilles, and Spanish Country Dances at his Waltz and Cotillon Academy (Courier, 27th May 1816)9. Spanish country dances formed a new genre, distinctive in that the first couple was improper (1st lady on the gentlemen’s line, and the 1st gentleman on the ladies’ line) and the tunes were either in 3/8 or 6/8 time. This initiated a spate of Spanish dances with a number of collections being published over the next few years. Spanish dances became a standard component in the repertoire of dancing masters throughout the nineteenth century.

Mademoiselle Duvernay is wearing the pink, frilled Spanish-style dress worn by Florinda in the ballet The Devil on Two Sticks to dance the Cachucha 12. Reports of her “exceedingly graceful and pleasing” dance reached Sydney in 1837.

Another aspect of the Spanish dance genre was the inclusion of solo and couples dances: the bolero, and cuchuracha or guaracha. These dances were used on the stage, taught in dancing schools, and were presented as items at concerts, balls and dances. The young Princess Victoria (later Queen Victoria) was an enthusiastic theatre-goer and one of her favourite performers was the dancer Pauline Duvernay. Durvernay was extremely popular in the role of Florinda, the heroine of Jean Coralli’s 1836 ballet Le Diable Boîteaux (The Devil on Two Sticks or The Lame Devil), where she danced the Cachucha – “the high-spot of the ballet” 11. Reports of Mademoiselle Durvenay’s charming dancing “which was enchored [sic] with expressions of vehement admiration and delight” reached Australia in 1837 13. Such was the acceptance of the dance form into polite society that Queen Victoria herself “was very much pleased indeed” when her daughter, Princess Alice learnt the Spanish Guaracha (with castanets) and commended it as “an excellent exercise for improving the figure and teaching graceful motion”14.

Australia

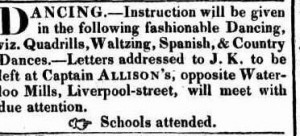

The first advertisement in the colony offering Spanish Dances. Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser (1823, August 2) 15.

In the colony, Spanish dances were first advertised, along with other fashionable dances, as being taught in Hobart in 1823. Socially, the first Spanish waltzes were reported in Sydney at Sir John Jamison’s ball in 1824 16.

Many veterans of the Peninsular Wars came to Australia. Apart from thousands of ordinary soldiers and sailors, the governors Brisbane, Darling, Bourke, and Gipps; and William Light, the founder of Adelaide, had all served in the wars. Any of the balls held in the first half of the colonial era, where country dances were frequently mentioned, may have included this dance.

An Officer of the 40th Regiment, 1826 17. Most of the officers would have been accomplished in the art of dance, an essential social grace. Dancing masters often taught both fencing and dancing.

In the year 1828 the Officers of the 40th Regiment gave a ball in Hobart, which featured quadrilles and Spanish dances. The 40th Regiment was one of only three regiments to serve throughout the entire Peninsula campaign and thus was present at the battles of Salamanca and Talavera.

This evening the spacious apartments recently erected in the Barrack-square, were thrown open by the Officers of the 40th Regiment, to a numerous and fashionable assemblage of their friends, for a splendid Ball and Supper, to which most of the principal inhabitants had received cards.

The rooms filled soon after 10 o’clock; and quadrilles and Spanish dances were kept up during the whole night with great spirit. The Mess room was appropriated to dancing. It was brilliantly illuminated, and the floor was well and very tastily painted. In one part of the room was a handsome transparency. At the upper end were the present colours, whilst over the transparency were placed the old and venerable relics of those, which formerly accompanied the regiment to so many fields of glory. The Band was stationed outside, in a balcony, at one end of the room. In the larger of the rooms adjoining, were three or four card tables; the other was a refreshment room; and a third apartment was used as a cloaking room.

The Officers’ Mess built in 1827 at the Anglesea Barracks. The Military Museum of Tasmania is recognized as one of Australia’s most significant historical military precincts. Photograph courtesy of John Lennox.

At half-past 12 the two large rooms below stairs were thrown open for the supper, which was of the most elegant description. These rooms were tastily decorated with shrubs and wreaths of flowers, and the stair-case leading to the rooms was completely arched over and ornamented in a similar manner. The arrangement of the whole reflected the greatest credit upon the hospitality of the regiment, and the taste of the managing committee 18.

Although there are hundreds of events in the early colony where country dances were recorded, the names of the actual dances remain a mystery. This dance has obvious connections with Salamanca, the Peninsular Wars and regimental life, but it is impossible to say with certainly that is was danced in the colony. However, dances of this type were definitely a significant element in our early culture.

The association between colonial life in Tasmania and the Peninsular Wars is a fascinating episode in Australian history. The 40th Regiment stationed in Hobart, and those who remained to settle, had a profound influence on the developing settlement, leaving a striking legacy which can now be experienced through this vibrant and memorable dance.

Music by Philip’s Dog: Roland Clarke (violin), Katie Lawton (violin), Rebecca Wright (Cello), Donald McKay (bodran). Recorded by Daniel Nelson, Amniote Audio & Lisa Meier, Harmonix Productions at SAE Studios, Brisbane. Mixed and Mastered by Daniel Nelson, Amniote Audio. Available on our CD

Country dance: Triple minor or three couple set

| A1 | 1-8 | 1st lady leads the other two ladies lead around behind the line of men and all return to place |

| A2 | 1-8 | 1st man leads the other two men around behind the line of ladies and all return to place. |

| B1 | 1-6 | 1st and 2nd couples poussette to change places* |

| 7-8 | 1st couple advance to their 1st corners | |

| B2 | 1-2 | Set to 1st corners. pas de bourrée derriere or simple setting. |

| 3-4 | 1st couple dance round each other clockwise, maintaining their back to back position, to face 2nd corners | |

| 5-6 | Set to 2nd corners Pas de bourrée derriere or simple setting. |

|

| 7-8 | 1st couple dance round each other clockwise, maintaining their back to back position to end in 2nd place on their own side. | |

| C1 | 1-8 | All circle left and right |

| C2 | 1-8 | 1st couple figure of eight on opposite sides. 1st couple cross left shoulder, go around 1st corner by the right shoulder, pass 2nd corner by the left shoulder and back to 2nd place on their own side. |

*Poussette

This is a figure of progression – couples move around each other anti-clockwise 1½ times to change places.

Hold two hands with partner

Keep facing them throughout

Men keep facing the ladies side 0f the dance and ladies keep facing the men’s side of the dance.

Pas de bourrée derriere

Hop on left foot, pass right foot behind, step on left, close right behind. Repeat starting with a hop on right foot.

In a 3 couple set

The dance may be executed as a three couple set. In this case, dance the last 8 bars thus:

1st couple cross left shoulder, cast up around the 2nd couple, meet and dance down between 2nd couple, separate and dance down outside the 3rd couple (who move up), cross at the bottom to own side.

NB. The lady, now in 3rd place, immediately joins the next turn of the dance with the 3 ladies leading around.

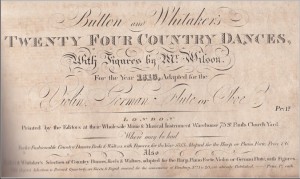

The Salamanca Castanets.

Dance manuals of the period included the music and brief instructions for each dance.

Links

Anglesea Barracks. http://armymuseumtasmania.org.au/

History of Salamanca Place. http://about-salamanca.com.au/salamanca-history/

Playlist of videos of people around the world enjoying our dance Salamanca Castanets https://www.youtube.com/@earlyaustraliancolonialdan6113/playlists

Notes

1 Button and Whitaker’s Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1813. The Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/ButtonWhitaker24CD1813

2 Eaton, H. G. (Henry Green), 1818-1887. The new wharf, Hobart Town, from the Ordinance Stores, taken from a sketch made at the time of the Regatta [picture]. With permission from National Library of Australia, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135290754

3 ‘Battle of Salamanca, 22nd July 1812, Wellington in the midst of the battle’

Coloured aquatint by J C Stadler after William Heath, published by Thomas Tegg, 1 April 1818. NAM. 1971-02-33-550-15

http://www.nam.ac.uk/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/britains-greatest-battles/salamanca

4 Majos and Majas dancing at Fair of Rocio.

L’Espagne / par Le Baron CH. Davillier ; ilustrée de 309 gravures dessinées su bois par Gustave Doré. – Paris : Librairie Hachette, 1874. – 799 p. : il.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3A%22Majos_et_majas_revenant_de_la_Feria_del_Roc%C3%ADo_(environs_de_S%C3%A9ville)%22_(19316302233).jpg

5 Majos. A description of majo and maja in Spanish culture. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Majo

6 Noah, M. M. (1819). Travels in England, France, Spain, and the Barbary States in the years 1813-14 and 15. New-York: Kirk and Mercein.

Mordecai Manuel Noah was an American playwright, diplomat, journalist, and utopian. He was born in a family of Portuguese Sephardic ancestry.

7 Dutton, Kenneth. (2010) That Gallant Gentleman. The Remarkable Story of Colonel Charles George Gray. Central Queensland University Press. Pp56-70

8 Spanish Arts: Dance and Music: fandango. Accessed 2/2/2016

http://www.spanish-art.org/spanish-dance-fandango.html

9 Jerome Robbins Dance Division, From The New York Public Library. Boliero published in Dublin (1800 – 1809). Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1b3d8670-fce0-0132-7b09-58d385a7bbd0

10 Cooper, Paul. Edward Payne, Dancing Master (?-1819). Accessed 2/02/2016.

http://regencydances.org/paper009.php

11 Pauline Duvernay as Florinda in Le Diable Boîteux. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O102518/pauline-duvernay-as-florinda-in-print-lewis-john-frederick/

12 ibid.

13 DRURY LANE THEATRE. (1837, April 19). The Sydney Monitor (NSW : 1828 – 1838), p. 4 (EVENING). Retrieved March 3, 2016, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32155652

14 Lowe, J. (1992). A New Most Excellent Dancing Master: The Journal of Joseph Lowe’s Visits to Balmoral and Windsor (1852-1860) to Teach Dance to the Family of Queen Victoria: Pendragon Press. p.87

15 Classified Advertising. (1823, August 2). Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser (Tas. : 1821 – 1825), p. 2. Retrieved December 21, 2015, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1089941

Also

Classified Advertising. (1823, September 6). Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser (Tas. : 1821 – 1825), p. 1. Retrieved December 26, 2015, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1089962

16 Sir John Jamison’s Ball & Supper THE FASHIONABLE WORLD. (1824, July 1). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), p. 2. Retrieved February 1, 2016, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2183020

17 Officer, Light Company, 40th Regiment of Foot, 1826. Historical Records of the 40th (2nd Somerset Regiment. Raymond Smythies, Cpt. R. H. Public Domain. Retrieved March 2, 2016, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Officer_light_company_40th_reg_of_foot_1826.jpg

18 EXTRACTS FROM A JOURNAL. (1828, March 22). The Hobart Town Courier (Tas. : 1827 – 1839), p. 3. Retrieved February 21, 2016, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4223557

See also:

HIS MAJESTY’S FORTIETH REGIMENT.—TASMANIAN GAIETY. (1828, April 2). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), p. 3. Retrieved February 21, 2016, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2190182

19 Map of Hobart, 1839. George Frankland. Record ID: SD_ILS:548683

Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

https://stors.tas.gov.au/AUTAS001131821480

Also

Lennox, J., Wadsley, John. (2011). Barrack Hill : a history of Anglesea Barracks 1811-2011. Canberra: Corporate Graphics – Defence Publishing Service.

Map of Hobart, 1839. Showing the proximity between Salamanca Place and the Barracks. Courtesy Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office. 19

______________________________________________________________

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Heather Clarke.

8 Responses to Salamanca Castanets