…they should not at first be alarmed with the report of Guns, Drums, or even a trumpet. – But if there are other Instruments of Music on board they should be first entertained near the Shore with a soft Air.

Lord Morton (1767)1

On the eve of Cook’s first voyage of discovery, the president of the Royal Society developed a list of hints for “the consideration of Captain Cooke, Mr. Bankes, Doctor Solander, and the other Gentlemen who go upon the Expedition on Board the Endeavour.”1 This list reveals the thoughts of a philosopher of the Enlightenment with visionary ideas well ahead of his time.

James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton 2 (1702–1768) provided a list of humanitarian hints to Lieutenant Cook and the gentlemen on the Endeavour.

James Douglas was the 14th Earl of Morton, a Scottish peer dedicated to science with a keen interest in astronomy. He was a founding member and President of the Society for Improving Arts and Sciences in Edinburgh, and elected as President of the Royal Society in London in 1763. Morton recognised the importance of observing the transit of Venus, and was influential in obtaining a grant of £4,000 to finance Cook’s first voyage.

Just weeks before the Endeavour was due to sail, Captain Samuel Wallis returned from an exploratory voyage in the Pacific with crucial information about the island of Tahiti. The island’s location in the southern hemisphere was quickly acknowledged as the perfect spot for observing the transit of Venus. Wallis also provided detailed reports about his encounters with the islanders – the first meetings between Tahitians and Europeans.

The Natives of Otaheite Attacking Captain Wallis, artist unknown (1767).3

National Library of Australia [Public Domain] After an initial violent encounter, Wallis and the Tahitians established a friendly relationship.

…endeavour by every fair means to cultivate a friendship with the Natives and to treat them with all imaginable humanity.

…exercise the utmost patience and forbearance with respect to the Natives.

It seems Cook tried as much as possible to follow these hints, however, the reality of exploration with the urgent necessity of finding fresh food and water, combined with the problems of communicating with new people, presented many difficulties. At the time, Cook was regarded as unusual in his humanitarian ideals. It is apparent from his journals that he tried his utmost to act in accord with Morton’s hints. Cook cared for his men and did everything in his power to protect their lives. He cared for the people he met and was adept on many occasions in transforming “a dangerous confrontation with the indigenous people into one of cautious understanding and respect between two distinctly different cultures”. 4 It is clear from his writings that hated the choice between protecting his men from attack, and firing on Indigenous people. His grief was palpable when someone died, whatever their race. He worried about the exploitation, cultural damage, and diseases which could come about from his contact.5

...check the petulance of the Sailors

An exceptional feature of Cook’s philosophy was his attitude to women. He believed all women deserved respect, whether in England or on a Pacific Island.

A young woman of Otaheite dancing.6

National Library of Australia.

Cook tried to control his crew and protect Indigenous women.

It was generally the custom for European explorers to allow their men the freedom to fulfill their desires with Indigenous women, however, Cook set in place firm regulations to prevent his men from taking advantage of such women. He believed it was callous and unethical to contaminate the locals with the sexually transmitted diseases his crew inevitably carried.7 This view was extremely unpopular with his men who believed sex was a reward after the deprivations of a long voyage and for some, it had been a motivating factor in signing on for the voyage. Cook did his utmost to protect island women from unwanted sexual advances, and on his second voyage, flogged five men for being “too free with the women”.8

Another issue which Morton addressed in his guidelines would have changed the course of history enormously, had it been adhered to:

They are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit.

No European Nation has a right to occupy any part of their country, or settle among them without their voluntary consent. Conquest over such people can give no just title, because they could never be the Aggressors.

Despite Morton’s profound statement, the race for colonisation by European countries was intense, and if not the British, then the French or the Spanish would soon have began colonies in the Pacific. Today, we can only look back over the course of history and marvel at Lord Morton’s insights.

Soft Airs

Included in list of hints, is this remarkable guidance:

…they should not at first be alarmed with the report of Guns, Drums, or even a trumpet. But if there are other Instruments of Music on board they should be first entertained near the Shore with a soft Air.

Both music and dance played important roles in Pacific encounters. It was understood that music had the power to calm and entertain, and the sharing of dances fostered a sense of camaraderie, especially as each group joined in the others’ dance. Ships always had musicians onboard: commonly fiddlers, drummers, and fifers. On the Endeavour, the only musician listed was the fiddler, Thomas Rossiter. On subsequent voyages, the Admiralty recognised the importance of music in cross-cultural encounters and trained and employed considerably more musicians. The bands included French Horns, flutes, violins, hautboys (oboes), Highland bagpipes, trumpets, and drums. Apparently the Tahitians were especially delighted with the music of the Highland pipes.

Morton’s Legacy

The Earl of Morton was devoted to the study of science and did his utmost to encourage and support scientific research. As well as the role of President for the Society for Improving Arts and Sciences in Edinburgh, and the Royal Society in London, he was a commissioner on the Board of Longitude and one of the first trustees of the British Museum.

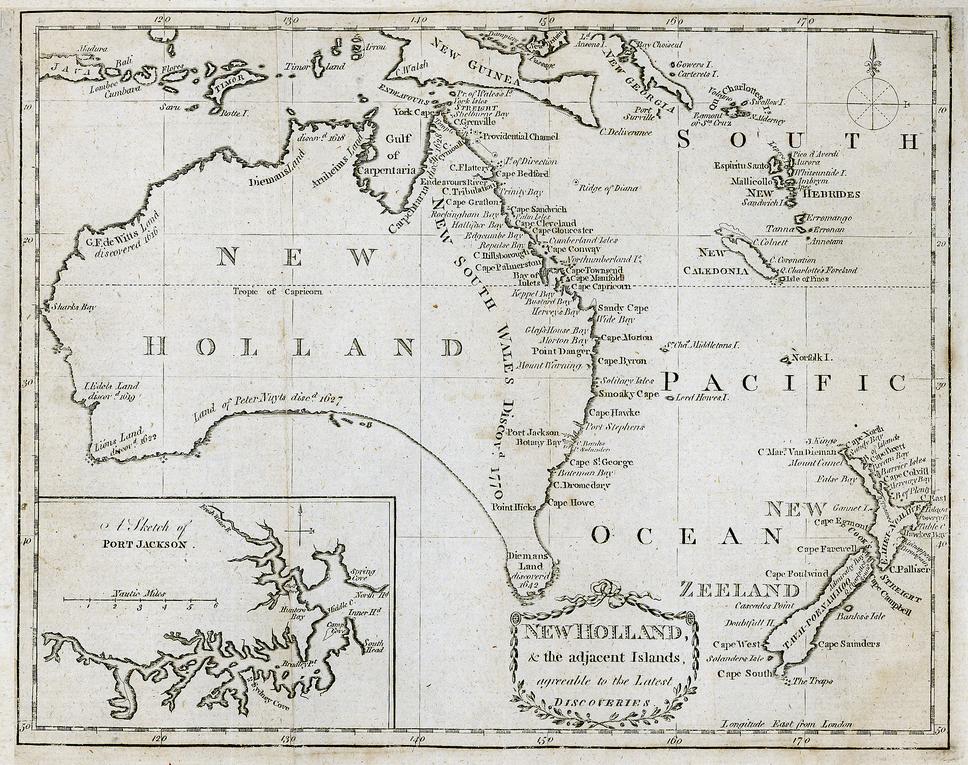

Morton did not live to hear about Cook’s voyages, the people he encountered, or the consequences of the list of hints. He died on 12 October 1768, six weeks after the Endeavour set sail. Cook paid tribute to the Earl on 16th May 1770, naming Cape Morton, and Moreton Bay in Queensland in his honour. Due to a transcription error in the published account of Cook’s voyage in the Endeavour, the spelling of the Bay was altered to Moreton and this is currently the accepted version.

The original map in Cook’s journal accurately shows the spelling for ‘Morton Bay” but a transcription error in the text led to the current spelling of ‘Moreton Bay”.

Detail from a Map of New Holland from 1790.9

National Library of Australia.

Dance

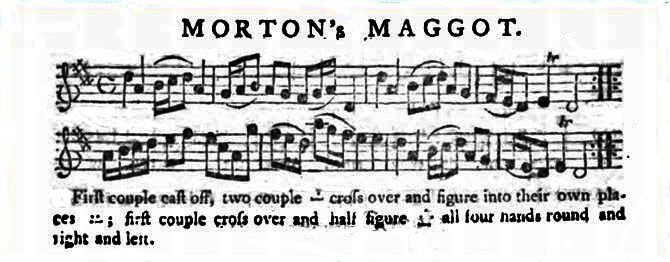

In the 18th century, dances were frequently devised to celebrate significant events. In Lord Morton’s case, a dance entitled Morton’s Maggot was published in 1744. Although it is impossible to state with certainty that this dance was connected to the Earl of Morton, it seems highly probable that it marked a major event in his life, for in 1742, Morton obtained an act of parliament vesting the ownership of Orkney and Shetland in himself and heirs. It could often take a year or two for a dance to be devised and published after a noteworthy occasion, making Morton’s Maggot a likely candidate. At the time, the word “maggot” meant a favourite, a extravagant notion, or a whim –in this case, Morton’s Maggot translates as Morton’s Favourite Dance.

Listen to tune:

Morton’s Maggot transcribed and recorded by Roland Clarke.

Dance instructions and score for Morton’s Maggot.

The Gentleman’s Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, Volume 23. (1753)10

maggot = favourite or whim.

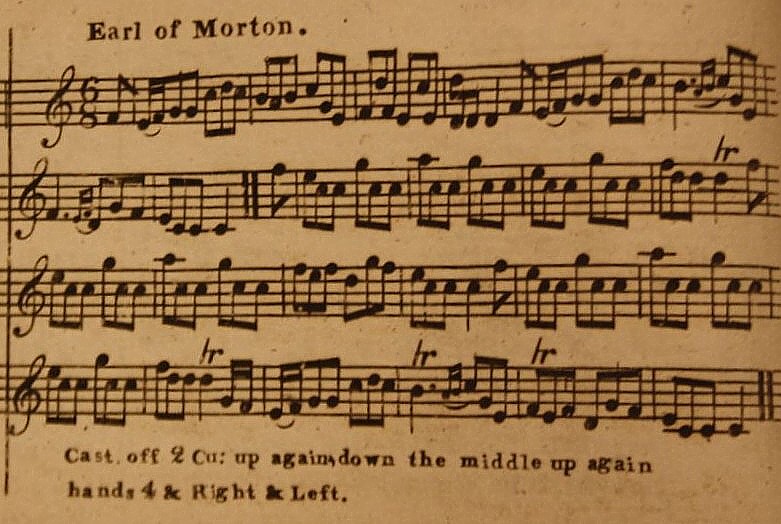

Music

A tune directly related the Earl of Morton’s family was published by the famous Scottish fiddler, Neil Gow in 1792. The tune The Earl of Morton’s Jig appeared in A third collection of Strathspeys, Reels &c. Gow was patronised by the nobility and this tune indicates the sponsorship of one of the Earls of Morton, either James Douglas himself, his son, Sholto Charles Douglas (1732 – 1774) 15th Earl of Morton , or most likely, his grandson, George (1761 – 1827) 16th Earl of Morton. This remains a well known Scottish tune to this day.

Listen to tune:

The Earl of Morton’s Jig transcribed and recorded by Roland Clarke.

The Earl of Morton’s Jig with simple dance instructions typical of the period.

Cahusac’s Annual Collection of Twenty-four Favourite Country Dances for the Year 1811.

Another tune and dance attributed to the Douglas family is Lady Mary Douglas’ Reel, still a popular Scottish country dance. In the family portrait of the Douglas family from 1740, Lady Mary is depicted as a three year old, holding a doll.

James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton with his family in 1740.11

His daughter inspired the well-known Scottish dance and tune Lady Mary Douglas.

References

1 Hints offered to the consideration of Captain Cook. MS 9-Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, 1745-1923 (bulk 1745-1820) [manuscript]./Series 3/Item 113 _ 113h

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-223065342/view

2 Detail from portrait of James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, portrait with his family by Jeremiah Davison, 1740. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_Douglas_Davison.jpg [Public domain]. The original is in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/8209/james-douglas-14th-earl-morton-1702-1768-and-his-family

3 The Natives of Otaheite Attacking Captain Wallis the First Discoverer of That Island by an unknown artist (1767) Public Domain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Wallis

National Library of Australia. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1046598

4 Mundle, R., & Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2013). Cook: from sailor to legend. Sydney, NSW: ABC Books. p. 222

5 Collingridge, V. (2003). Captain Cook Obsession and Betrayal in the New World. Great Britain: Ebury Press.

6 Sherwin, J. K. & Cook, James. & Webber, John. (1784). A young woman of Otaheite dancing. National Library of Australia http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136182951

7 Collingridge, V. (2003). Captain Cook Obsession and Betrayal in the New World. Great Britain: Ebury Press. p. 289

8 Collingridge, V. p.288

9 Map (1790). New Holland & the adjacent islands, agreeable to the latest discoveries. National Library of Australia http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232607560

10 The Gentleman’s Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, Volume 23. (1753)

11 James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, portrait with his family by Jeremiah Davison, 1740. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_Douglas_Davison.jpg [Public domain]. The original is in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/8209/james-douglas-14th-earl-morton-1702-1768-and-his-family

Select Bibliography

Agnew, V. (2001). A Scots Orpheus in the South Seas: Encounter music on Cook’s second voyage. Journal for Maritime Research, 3(1), 1-27.

Clarke, H. B. (2014). Captain Cook’s Country Dance. Australian Folklore, 29(November 2014), 71-86.

Cook, J., King, J., Douglas, J., Cadell, T., Nicol, G., & Hughs, M. (1785). A voyage to the Pacific Ocean : undertaken by the command of His Majesty, for making discoveries in the northern hemisphere : performed under the direction of Captains Cook, Clerke, and Gore, in His Majesty’s ships the Resolution and Discovery ; in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779 and 1780 : in three volumes. London: Printed by M. Hughs, for G. Nicol … and T. Cadell …

Horwitz, T. (2002). Blue latitudes: boldly going where Captain Cook has gone before. New York: H. Holt.

Keller, R. M. (2006). Dance Figures Index: English Country Dances, 1650-1833. from The Colonial Music Institute https://www.cdss.org/elibrary/DFIE/Index.htm

Mellor, D. (2006). Cook, his mission and Indigenous Australia: a perspective on consequence. Paper presented at the Cook’s Pacific Encounters symposium, National Library of Australia. https://www.nma.gov.au/audio/captain-james-cook-series/transcripts/cook-his-mission-and-indigenous-australia

Mundle, R., & Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2013). Cook: from sailor to legend. Sydney, NSW: ABC Books.

Salmond, A. (2003). The Trial of the Cannibal Dog. Captain Cook in the South Seas

London: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books.

Vian, A. R. (1885). Dictionary of National Biography (Vol. Volume 15): Smith, Elder & Co.

______________________________________________________________

This resource was created on the lands of the Gubbi Gubbi people.

We pay our respects to their elders past and present.

Sovereignty was never ceded.

______________________________________________________________

Header credits:

1. Portrait of Captain Cook by Nathaniel Dance-Holland [Public domain]

2. A jig on board by Cruikshank. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

3. View of the South Seas by John Cleveley the Younger [Public domain]

______________________________________________________________

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke.

2 Responses to Lord Morton’s hints