The First Nations people have a rich and diverse culture extending for many thousands of years – considered to be the oldest continuous culture in the world. In this unbroken cultural legacy, dance has always played an important role, helping to tell the stories of the past and the present, and continuing strong into the future. The historical records of their dances available to us come from the European perspective, and thus were often highly biased. It is with some trepidation that we venture into this subject, not wishing to perpetuate the harmful attitudes of the past. We understand that protecting this cultural heritage is vitally important and we hope some of the resources presented here may help in this regard.

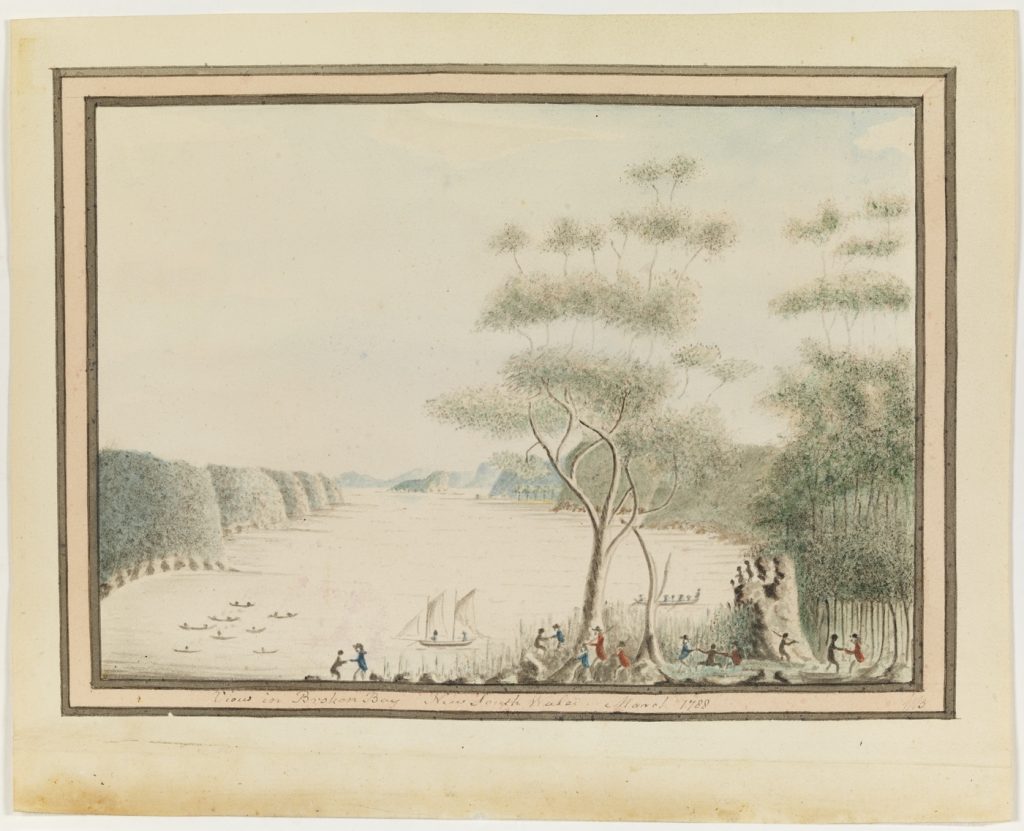

Some of the earliest records of First Nations people dancing with the settlers come from the writings of officers in 1788. A few days after landfall, Lieutenant William Bradley recorded his first meeting with the Indigenous people. After describing the initial phases of the engagement, he related how the participants joined hands and danced together. Two months later he depicted this encounter in the watercolour View in Broken Bay.

Historian and anthropologist, Inga Clendinnen claimed that this illustration portrayed dancing in the British style with the colonists taking the initiative, rather than adopting the local mode of dancing. Other accounts revealed that the British did participate in the local dances with both sides imitating the other’s movements.

they … always appeard Chearfull & good humour’d, they danced & sung with us, & imitated our Words and Motions as we did them”

John Hunter, Journal kept on board the Sirius during a voyage to New South Wales May 1787 – March 1791. (p.40)

Drawing upon evidence from the early journals of the colony, dancing was reported regularly amongst the convict community and that they also danced with the Indigenous people. This important finding highlights the significant nature of dance as a non-aggressive and cross cultural social activity, and clearly demonstrates the role of social dance in the early colony as a means to develop social cohesion.

Deputy judge advocate, David Collins reported:

Still, notwithstanding this appearance of hostility in some of the natives, others were more friendly. In one of the adjoining coves resided a family of them, who were visited by large parties of the convicts of both sexes on those days in which they were not wanted for labour, where they danced and sung with apparent good humour, and received such presents as they could afford to make them; but none of them would venture back with their visitors.

Collins, D. (1798). An account of the English colony in New South Wales.

Captain John Hunter also included a detailed description of a First Nations dance he witnessed, with admiration, in 1788:

… it was Observ’d that certain parties alternately led forward to the front, & and there exhibited with their utmost Skill all the various motions which with them seem’d to constitute the principal beautys of dancing, one of the most Striking of which was, that of placing their feet very wide apart, and by an extraordinary exertion of the Muscles of the thighs and & legs, mov’d the Knees, in a trembling & very surprising manner, such as none of us could imitate, which seem’d to Shew, that it requir’d mich practise to arrive at any degree of perfection in it – There appeared a good deal of Variety in their different dances…

John Hunter, Journal kept on board the Sirius during a voyage to New South Wales. (p.171)

Although the British dances of 1788 are mostly unknown to the majority of Australians, the cultural heritage of the First Nations people remains strong.

In 2014, the Bangarra Dance Theatre, Australia’s leading indigenous performing arts company, celebrated their 25th anniversary with the inspirational story of Patyegarang, the First Nations woman who befriended the colony’s timekeeper, Lieutenant William Dawes. Dawes arrived with the First Fleet, and with the aid of Patyegarang created what is now considered to be the first written account of the Aboriginal language of Sydney.

Patyegarang was a young woman of fierce and endearing audacity, and a ‘chosen one’, so to speak, within her clan and community. Her tremendous display of trust in Dawes resulted in a gift of cultural knowledge back to her people almost 200 years later and I feel her presence around us, with us as we create this new work.

Stephen Page, artistic director of Bangarra Dance Theatre.

References

Bangarra Dance Theatre. (2014) Patyegarang. https://www.bangarra.com.au/productions/patyegarang

Blasdale Clarke, Heather Evelyn (2018). Social dance and early Australian settlement: An historical examination of the role of social dance for convicts and the ‘lower orders’ in the period between 1788 and 1840. Queensland University of Technology

Clendinnen, I. (2003). Dancing with strangers. Melbourne: Text Pub.

Collins, David. (1798). An account of the English colony in New South Wales. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12565/12565-h/12565-h.htm

The Notebooks of William Dawes on the Aboriginal language of Sydney. https://www.williamdawes.org/patyegarang.html

Hunter, John. Journal kept on board the Sirius during a voyage to New South Wales, May 1787 – March 1791. https://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2015/D06318/a1518.html