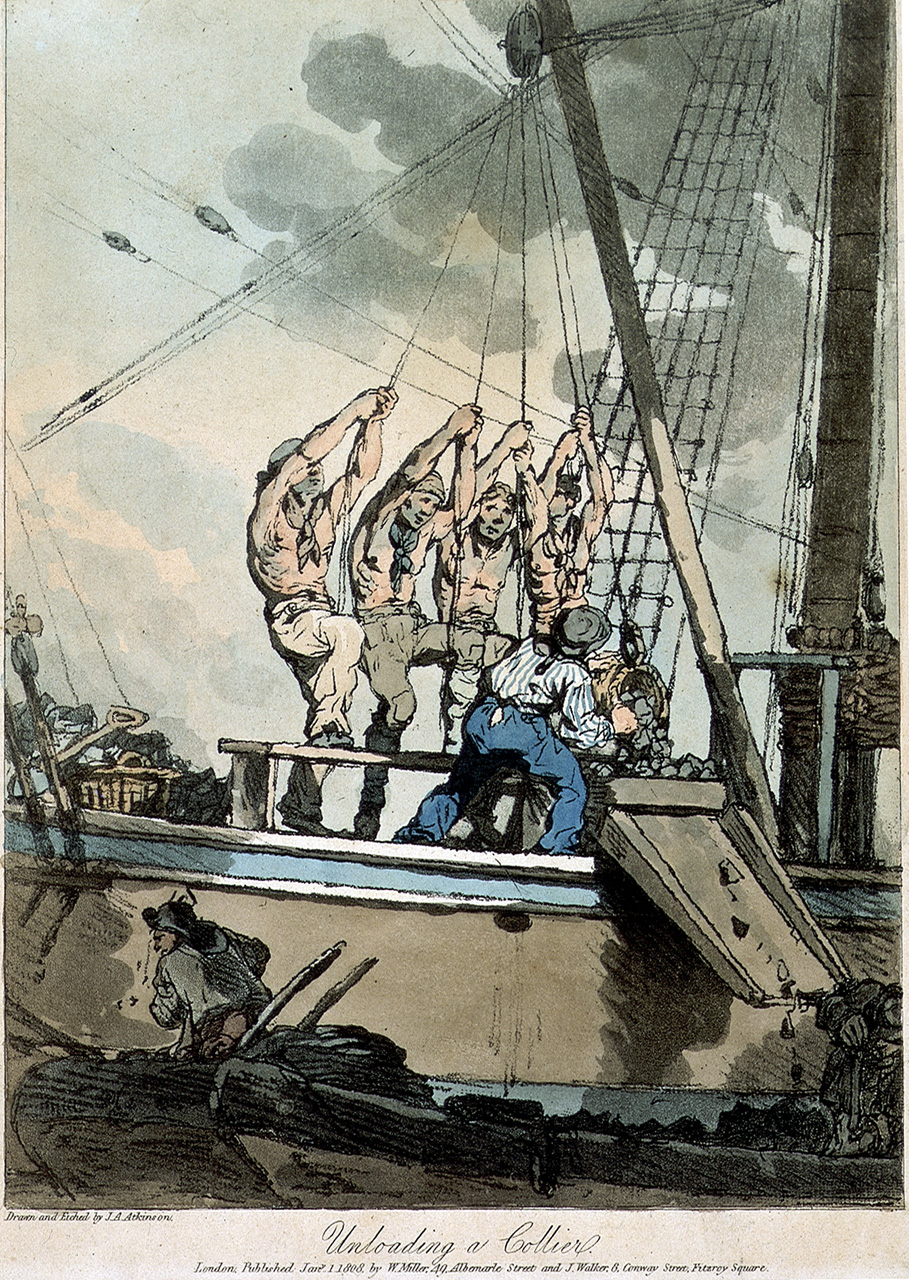

At the age of 18, James Cook followed his heart’s desire and took to life at sea. He was apprenticed to the well-respected Walker brothers in Whitby on the Yorkshire coast. John and Henry Walker had a fleet of cargo vessels specialising in the transport of coal from Newcastle-on-Tyne to London, a round trip of approximately 600 nautical miles taking 4 weeks to complete. Sailing in this area was notoriously dangerous with submerged rocks, shifting sand banks, rough seas, strong tides and fierce storms – perfect training for an explorer in the south seas.

As an apprentice Cook learnt the skills necessary to master a collier: navigation, the overall maintenance of rigging and sails, the fitting-out required for a new vessel, and the daily rigours of sailing. He studied diligently and applied himself to the additional areas of algebra, astronomy, geometry and trigonometry. On board he was required to undertake the hard physical labour of working the ship, including the demanding task of loading and unloading coal, a grimy job which took up to a week in each port.

James experienced all aspects of the seaman’s trade, including the harsh realities of shipboard life. Courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

James completed his training, attained the rating of Mate, and was offered a secure position as master of Walker’s collier Friendship. Despite this promising future, the young man declined the offer and instead enlisted in the Royal Navy.

Due to the impending war with France, the navy needed men for their warships. Press-gangs scoured the ports for victims, often merchant seamen, who they could ‘impress’ or force into service. The Navy had a huge demand for manpower: not only were large crews required for each man-of-war, but there was a high mortality rate. This was due, not so much to death in battle, but to illnesses caused by the poor diet and terrible conditions.

Although there is speculation that Cook may have joined the Navy to avoid the press-gang, thus volunteering on more advantageous terms, his friend and mentor, John Walker asserted that James had always wanted to enlist. The Navy offered more opportunities for a man of Cook’s abilities – there was the promise of further promotion and the allure of adventure in distant places.

Press-gangs captured skilled seamen and forced them into service in the Royal Navy. The need to find recruits became desperate when war with France was imminent. It was declared in May 1756, the year after James enlisted. Courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

The tall, strongly built James Cook joined the Royal Navy in June 1755 as a common seaman at the age of twenty-six. His talent and expertise were quickly recognised and within a month he was promoted to master’s mate. By 1758, Cook had been promoted to master of the Pembroke and had joined Admiral Boscawen’s Fleet in the campaign against the French for the conquest of Canada.

Dancing in the Royal Navy

Dancing was a regular activity on board the ships of the Royal Navy. The historian, N. A. M. Rodger wrote of the importance of music and dance as a source of entertainment and exercise for the seamen, and as a way of maintaining a connection with home. Dance was a part of Georgian Naval life both above and below deck. Reports tell of the dancing of jigs and reels all night to celebrate the completion of a successful voyage 1, of a sailor dancing on a hatch cover on a sunny summer’s day 2, and of Sir Edward Pellew kidnapping a negro violinist “to furnish music for the sailors’ dancing in their evening leisure, a recreation highly favourable to the preservation of their good spirits and contentment.”3

As it was a common everyday activity it often escaped comment, however, it was mentioned by Admiral Boscawen with a pleasant recollection:

In Boscawen’s flagship as they sailed westward across the Atlantic in the mild spring of 1755, the men danced nightly to fiddle, fife and drum. It reminded the admiral as he wrote home to his wife, of country dances with her in former years.4

Admiral Edward Boscawen (1711-1761) wrote of his crew dancing every night as they crossed the Atlantic in 1755. Portrait by Joshua Reynolds c. 1755

Boscawen was known as a man of action and a courageous leader with “a rare concern for the welfare of common seamen.”5 He had two nicknames: wry-necked dick for his habit of carrying his head on one side due to a neck injury sustained in battle; and Old Dreadnought after one of his first ships. Evidently, the latter “was the nickname his sailors dearly loved to call him.”6

One story relates an incident when, under the necessity of going into a boat to shift his flag from his own ship to another … a shot went through the boat’s side, whereupon the admiral, taking off his wig, stopped the leak with it, and by this means saved the boat from sinking.7 He is also famed for the statement, “Never fire, my lads, till you see the whites of the Frenchmen’s eyes.” 8

Celebrated in dance

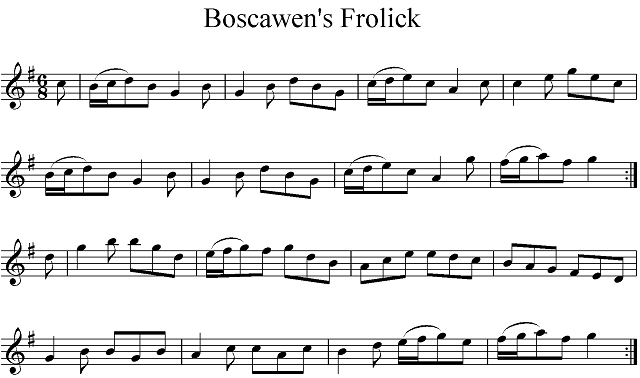

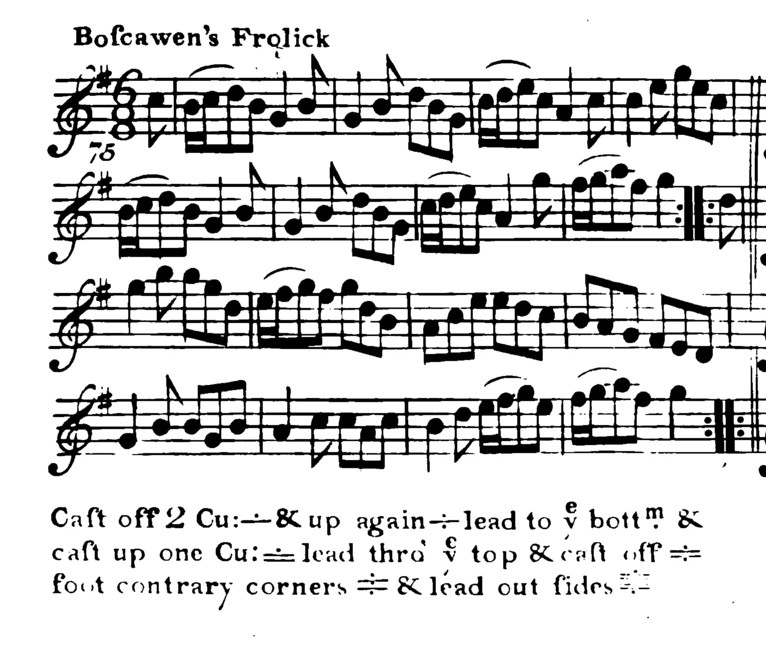

Country dances were commonly devised to celebrate important events. Boscawen’s naval victory at the Battle of Lagos in 1759, saving England from French invasion, was an extremely significant incident at the time. The dance Boscawen’s Frolick was published in Thompson’s Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1761 and again in Thompson’s Compleat Collection of 200 Fashionable Country Dances, 1765. 9

The Battle of Lagos between Britain and France took place over two days, on 18 and 19 August 1759 near Lagos, Portugal. The Rt Honble Edwd Admiral Boscawen was hailed as a hero for defeating the planned French invasion of Britain. Courtesy of National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

In the year the dance was first published, Admiral Edward Boscawen died at the age of 50 after contracting typhoid fever. His genteel and highly educated wife, Frances, valued and preserved his letters; these now provide a notable insight into life on board an 18th century ship.10

Impressed by Boscawen’s example, James Cook, as the captain of three voyages of discovery, also demonstrated great care for the lives and health of his crew. And like Boscawen, he encouraged the dancing of hornpipes and country dances onboard his ships whenever the weather was fair.

Listen to Boscawen’s Frolic as a midi or mp3 Arranged by Roland Clarke 2014. Now available on our CD

Country dance: triple minor longways.*

| A1 | 1-8 | 1st couple cast off down the outside and back. |

| A2 | 1-4 | 1st couple lead down below 3rd couple (2nd couple moving up), cast up to 2nd place. |

| 5-8 | 1st couple lead up and cast into 2nd place, to face first corners. | |

| B1 | 1-4 | Frolick (set or foot) to 1st corners. |

| B1 | 5-8 | Frolick (set or foot) to 2nd corners. |

| B2 | 1-8 | Lead out men’s side, separate and cast back into centre. Lead out ladies’ side, separate and cast back into centre, turn two hands. |

*Notes on the dance.

- The first four sections of the dance have been modified to correspond to 16 bars of music (AA).

- While this is a triple minor dance, for modern taste it is recommended that it be danced in a four couple set.

- Footing is danced as a backstep: a backwards skip danced on the spot.

- Thank you to Anne Daye for dicussions on the interpretation of the dance.

______________________________________________________________

Sources

1 Gardner, J.A. Above and Under Hatches, C.C. Lloyd (London, 1955) p. 24 .” When the Panther paid off in 1782 the ship’s company gave a grand supper, with the lower deck illuminated and jigs and reels all night.” As quoted in The Wooden World. http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/6172135

2 Public Record Office, Admiralty Correspondence: ADM 1/920, enc. To E. Hawke, 3 Jun 1755. “Even in the rather unlikely situation of a press tender we hear of a mixed set of pressed men, volunteers, press gang and tender’s crew dancing on the hatch cover on a sunny summer’s day.” As quoted in The Wooden World.

3 The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954) 27 Aug 1855: 8. Web. 7 May 2014 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12973404>.

4 Rodger, N.A.M. The Wooden World. An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. Collins, London. 1986. http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/6172135

5 Dictionary of Canadian Biography; (University of Toronto Press). Vol. III (1741-1770), 1974

6 Drake and the Dons. (1916, July 27). The Gundagai Independent and Pastoral, Agricultural and Mining Advocate (NSW : 1898 – 1928), p. 3. Retrieved May 14, 2014, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122196228

7 ADMIRAL BOSCAWEN’S WIG. (1886, May 22). The Herald (Fremantle, WA : 1867 – 1886), p. 8 Supplement: SUPPLEMENT TO THE HERALD.. Retrieved May 14, 2014, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110070392

8 Viator (pseudn.), “Cornish Topography. To the Editors of the European Magazine.” The European Magazine, and London Review. March 1819 (Volume 75), p. 226 http://books.google.com.au/books?id=xxoYAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA226&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

9 Eger, Elizabeth. Boscawen , Frances Evelyn (1719–1805). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

10 Robert M. Keller, compiler. Dance Figures Index: English Country Dances, 1650-1833

https://www.cdss.org/elibrary/DFIE/Index.htm

11 Thompson’s Compleat collection of 200 favourite country dances: perform’d at Court Bath, Tunbridge & all publick assemblies with proper figures or directions, to each tune: set for the violin German flute & hautboy. Price 3/6, Vol. 2. [1765].

Eighteenth century collections online [electronic resource] via State Library of New South Wales. http://library.sl.nsw.gov.au/record=b2169903~S2

Select bibliography

Brunsman, D. A. (2013). The evil necessity : British naval impressment in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Collingridge, V. (2003). Captain Cook Obsession and Betrayal in the New World. Great Britain: Ebury Press.

Kippis, Andrew. (1725-1795) A narrative of the voyages round the world performed by Captain James Cook : with an account of his life during the previous and intervening periods. https://archive.org/details/cihm_16842/page/n15

Mundle, R., & Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2013). Cook: From sailor to legend. Sydney, NSW: ABC Books.

Robson, John. Captain Cook’s World. Maps of the Life and Voyages of James Cook R.N. Random House, Australia. 2000. p.17. http://trove.nla.gov.au/version/9727313

Suthren, V. (2000). To Go Upon Discovery: James Cook and Canada, from 1758 to 1779. Toronto: Dundrun Press.

Republished with permission.

2014 version of this page.

Captain Cook Society of Australia. Endeavour Lines Newsletter. Vol. 67 – October 2016.

______________________________________________________________

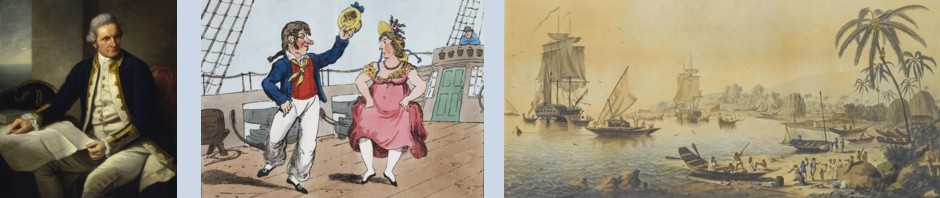

Header credits:

1. Portrait of Captain Cook by Nathaniel Dance-Holland [Public domain]

2. A jig on board by Cruikshank. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

3. View of the South Seas by John Cleveley the Younger [Public domain]

______________________________________________________________

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke.

Pingback: Sailor’s Hornpipe | Australian Historical Dance