Captain Cook wisely thought that dancing was of special use to sailors. This famous navigator, wishing to counteract disease on board his vessels as much as possible, took particular care, in calm weather, to make his sailors and marines dance to the sound of a violin, and it was to this practice that he mainly ascribed the sound health which his crew enjoyed during voyages of several years continuance. (Blasis, 1830)1

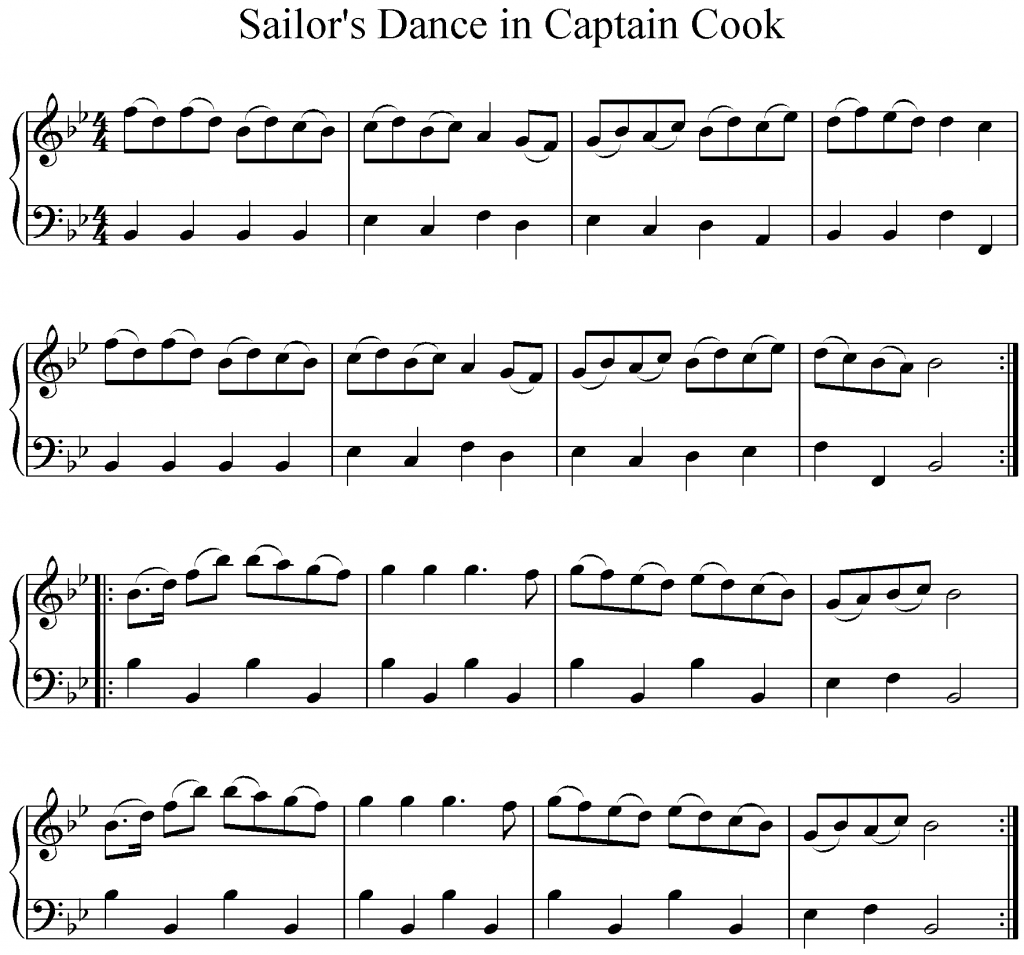

“Sailors Dance in Capt Cook”

From the Death of Captain Cook, probably the equestrian version staged in Edinburgh, 1790.

A Collection of Strathspeys, Reels, Jiggs, &c. Charles Duff, Dundee (1792)

Transcription and recording by Roland Clarke.

Sound Health

Sound Health

During the eighteenth century, the leading cause of death at sea was not war or shipwreck, but death by disease – primarily scurvy, resulting from a lack of vitamin C. When Admiral George Anson returned from his epic four year voyage into the Pacific in 1740-4, his crew had suffered an appalling loss of life, with almost 1,400 men of the 1,900 who sailed dying from disease. His ill-fated circumnavigation of the world was one of the worst medical disasters at sea.

Cook was aware of these horrific statistics, and he himself had experienced the devastating effects of scurvy on his voyage across the Atlantic as part of Boscawen’s Fleet. His ship HMS Pembroke lost 23 men to scurvy on the voyage to Nova Scotia and was delayed from joining the siege of Louisbourg due to the large number of the crew unfit for service.

The Dying Sailor by Thomas Rowlandson (c.1790).2

Rowlandson visited many naval bases and witnessed first hand the appalling conditions

endured by sailors.

Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

In planning the voyages to the South Seas, Cook and the Admiralty were keen to find a solution. A variety of experimental foods were provided including sauerkraut, essence of spruce, and malt, but it was actually Cook’s determination to supply the crew with fresh fruit and vegetables whenever possible which made the difference. Throughout his long voyages of exploration he was remarkably successful in keeping his men healthy, however, it was more than just good nutrition which kept his crew fit and active.

The captain paid rigorous attention to the cleanliness of the ship, ensuring it was regularly scrubbed and fumigated, the bedding washed and thoroughly dried, and the hold well ventilated. He insisted that each member of his crew bathe regularly, and it was everyone’s duty to ensure that conditions below deck remained as fresh and clean as possible. He introduced a work routine of three watches (rather than the standard four) which guaranteed every man had adequate rest.

British seamen in Cook’s era. Courtesy of Museum of the American Revolution. Reenactors Adam HL, Tyler Putman, Brandyn Charlton.

Another problem which had beset Anson’s voyage, and the men in Cook’s care while wintering in Nova Scotia, was the extreme cold. Without the provision of suitably warm clothing, many seamen suffered and died in the freezing conditions. Sometimes the men had only standard issue slops unsuitable for cold weather, and often they had no change of clothing, meaning they had no choice but to remain cold and wet. In the Pacific, Cook ensured his crew were provided with warm ‘fearnought’ jackets and trousers made of heavy woollen cloth. On their trip home from the second voyage one of his men, Thomas Perry, applauded Cook’s concern for the well-being of the crew, and the success of the voyage in song:

We are hearty and well and of good constitution

And have ranged the Globe round in the brave Resolution

Brave Captain Cook he was our Commander

Has conducted the ship from all eminent danger.We were all hearty seamen no cold did we fear

And we have from all sickness entirely kept clear

Thanks be to the Captain he has proved so good

Amongst all the Islands to give us fresh food.And when to old England my Brave Boys we arrive

We will tip off a Bottle to make us alive

We will toast Captain Cook with a loud song all round

Because that he has the South Continent found.Blessed be to his wife and his Family too

God prosper them all and well for to do

Bless’d be unto them so long as they shall live

And that is the wish to them I do give. 3

Cook was in the unusual position of having risen through the ranks and consequently was intensely aware of the hardships common sailors endured. As a naval commander he had both the power and the insight to change these conditions.

At home in Mile End after his second voyage, Cook wrote to the Royal Society describing his “Method for preserving the Health of the Crew.”4 He was acknowledged for developing an innovative regime which had maintained the health of his crew to an extraordinary extent – on his second voyage, no man had been lost to scurvy. In honour of his success he was awarded the prestigious Copley Medal for “outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science.”5

Dancing for sailors

Although Cook’s writings concentrated mainly on geographical, nautical, and scientific matters, he noted many occasions when the Pacific Islanders danced. Less commonly known is the fact that he encouraged his own crew to dance for their good health and morale.

There was a long tradition of sailors dancing on board ship, particularly when the day’s work was completed and the weather was calm. By the beginning of the 19th century the sailor’s hornpipe was recognised as the national dance of England.

Dancing was a useful for developing agility, balance, and endurance – the best dancers were notably the most accomplished sailors.

Image from Dancing, Frazer (1907).6

Almost every ship carried musicians, and singing and dancing were important pastimes. Ship’s musicians were primarily sailors who could play fiddle, flute, fife, trumpet, or drum; however, they were often not registered as musicians in the crew list. On Cook’s first voyage, the music was supplied by the fiddler Thomas Rossiter. On later voyages more musicians were trained and employed by the Admiralty to provide a band of French Horns, flutes, violins, hautboys (oboes), bagpipes (loved by Tahitians!), trumpets, and drums.

One aspect of the travels which generated intense interest in England was the descriptions of South Sea Islanders’ dancing. Their style of dance was completely different to anything seen before, and elicited much discussion, particularly where the dances were portrayed as lewd in nature [see Polynesian dance]. This facet was widely reported and aroused an immoderate degree of attention, leaving the English component of the cultural exchange largely unrecognised. From an 18th century perspective, there was no novelty in the dances of English sailors which were considered an everyday activity and quite commonplace.

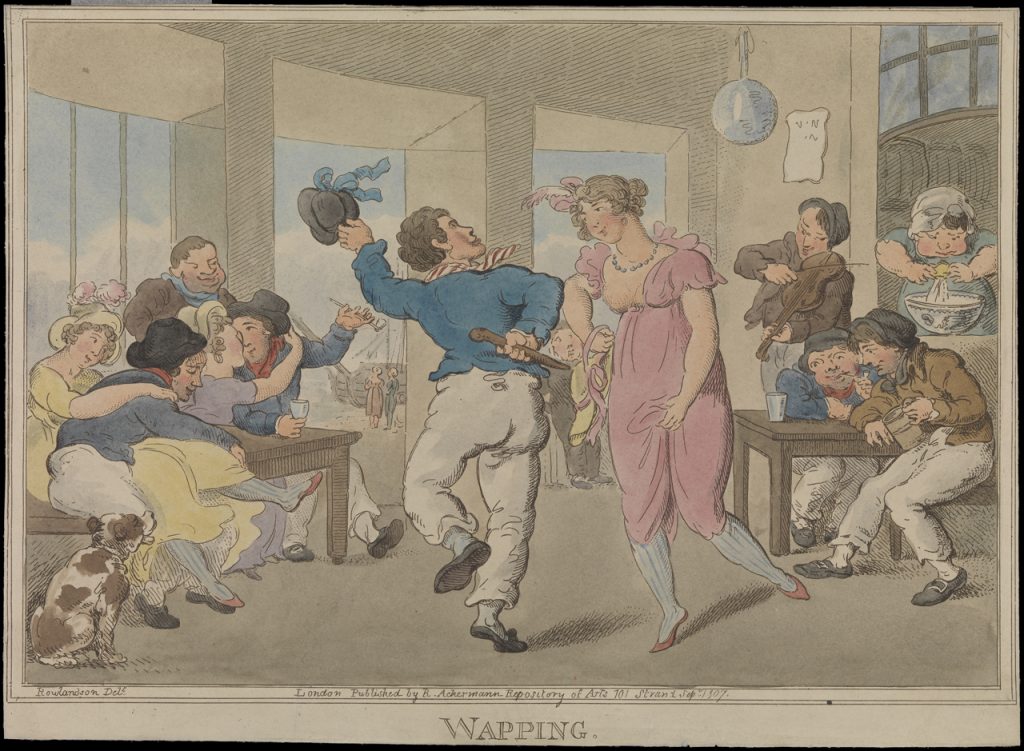

The Sailor’s Tavern in Wapping.7

William Dampier wrote that his sailors learnt to dance in the ‘musick houses’ in Wapping, a practise that continued into the early 20th century.

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

The dance historian, teacher, and writer, Carlo Blasis, was obviously impressed with Cook’s regime to encourage dancing and referred to it in The Code of Terpsichore (1828) and Notes upon Dancing, historical and practical (1847):

It was a maxim with Captain Cook, which proves the penetration of that extraordinary man, that dancing was of special service to sailors. That celebrated navigator, in his endeavours to counteract the inroad of disease on board his vessels, by every means in his power, took particular care in calm weather to make his sailors and marines dance to the sound of the violin, and it was to this practice that he mainly ascribed the sound health enjoyed by his crew, during voyages of several years’ continuance. The dance they generally indulged in, is called by the English the Hornpipe; it is of a most exhilarating character, and perhaps more animated even than the Tarantella. 8

Cook’s ships, especially on the first two voyages, were known as happy places and many of the crewmen joined him on subsequent trips. Notably, Cook’s practise of encouraging dancing was adopted by William Bligh, of Mutiny on the Bounty fame, who sailed as master of the Resolution on Cook’s third voyage. Captain Bligh in turn, passed on the knowledge to Matthew Flinders whose sailors also danced. During the era of transportation to Australia, a number surgeons in charge of convicts also encouraged dancing on deck, acknowledging its physical and psychological benefits. Today there is a large body of scientific research confirming the physical and psychological benefits of dancing.9

Incidents of the crew dancing were not well documented in Cook’s own journal but are clearly evident in journals of those who accompanied him. Many of his crew members kept accounts of their travels, particularly on Cook’s third voyage, and several recorded instances of the seamen dancing. Lieutenant John Rickman, wrote that “horn-pipes and country-dances after the English manner” were performed both on ship and on shore, and the local people also eagerly joined in with “with great good humour”.10 John Marra of the Resolution described the sailors dancing a hornpipe for King Ottoo in Tahiti; and the marine, John Ledyard, noted the crew dancing country dances and cotillions.

Although this element of Cook’s travels largely escaped notice, it was recognised in the theatre where it added an authentic and vibrant element to the staged depictions of the voyage. Both the pantomime Omai, or, a trip round the world, and the grand serious-pantomimic-ballet, The Death of Captain Cook featured dances for sailors, as well as items where the crew and the islanders danced together. See Polynesian Dance [soon to be posted] for more on the Islanders dancing.

Dancing the sailor’s hornpipe aboard the schooner, South Passage in Manly, QLD.

Filmed in 2020 for Dancing with Cook, a Primary School Education Unit.

STS (Sail Training Ship) South Passage is Queensland’s only owned and operated Tall Ship. Designed specifically for 14-17 year olds to experience “Adventure Under Sail” by the not-for-profit organisation the Sail Training Association of Queensland.

References

1 Blasis, C. (1830). The code of Terpsichore (R. Barton, Trans.). London: E. Bull.

2 Rowlandson, T. (c.1790). The Dying Sailor. Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1669921

3 Salmond, A. (2003). The Trial of the Cannibal Dog. Captain Cook in the South Seas London: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books.

Citing Cook in Beaglehole, ed., 1969, II:870.

4 Cook, J. (1776). A Method for Preserving the Health of the Crew of H.M.’s Ship the Resolution. Phil. Trans. R.S., 66:402.

Original In the British Library. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rstl.1776.0023

5 National Museum of Australia, Cook and the Royal Society, https://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/exploration-and-endeavour/cook-royal-society, viewed 26 April 2020

6 Frazer, L. G. L. (1907). Dancing. London: Longmans, Green. https://archive.org/details/dancingfrazer00fraziala/mode/2up

7 ‘Wapping’ by Thomas Rowlandson (1807) © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/127958.html

8 Blasis, C., & Barton, R. (1847). Notes upon Dancing, historical and practical … Followed by a history of the Royal and Imperial Academy of Dancing, at Milan. To which are added, Biographical Notices of the Blasis family, interspersed with various passages on theatrical art. Edited and translated … by R. Barton. With engravings. M. Delaporte: London.

9 Karkou, V., Oliver, S., & Lycouris, S. (Eds.). (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Wellbeing. New York: Oxford University Press

10 Rickman, J. (1781). Journal of Captain Cook’s last voyage to the Pacific Ocean, on Discovery: performed in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779 : illustrated with cuts, and a chart, shewing the tracts of the ships employed in this expedition. London: Printed for E. Newbery. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100268159

Select Bibliography

Agnew, V. (2001). A Scots Orpheus in the South Seas: Encounter music on Cook’s second voyage. Journal for Maritime Research, 3(1), 1-27.

Collingridge, V. (2003). Captain Cook Obsession and Betrayal in the New World. Great Britain: Ebury Press.

Ledyard, J. (1783). A journal of Captain Cook’s last voyage to the Pacific Ocean, and in quest of a North-west passage, between Asia & America: performed in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, and 1779 …. Hartford [Conn.]: Printed and sold by Nathaniel Patten. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100310610/Home

Kemp, P. (1970). The British Sailor: A social history of the lower deck. London: Aldine Press, J M Dent & sons. Ltd.

Rodger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World. An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. London: Collins.

Salmond, A. (2003). The Trial of the Cannibal Dog. Captain Cook in the South Seas

London: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books.

Suthren, V. (2000). To Go Upon Discovery: James Cook and Canada, from 1758 to 1779. Toronto: Dundrun Press.

Tilley, R. (2002). Australian Navigators. Picking up shells and catching butterflies in an age of revolution. Australia: Simon & Schuster.

Woodfield, I. (1995). English musicians in the age of exploration. Stuyvesant, N.Y.: Pendragon Press.

Yates, G. (1829). The Ball: or, a glance at Almack’s in 1829. London: Henry Colburn.

______________________________________________________________

This resource was created on the lands of the Gubbi Gubbi people.

We pay our respects to their elders past and present.

Sovereignty was never ceded.

______________________________________________________________

Header credits:

1. Portrait of Captain Cook by Nathaniel Dance-Holland [Public domain].

2. A jig on board by Cruikshank. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

3. View of the South Seas by John Cleveley the Younger [Public domain].

______________________________________________________________

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke.

2 Responses to Dancing for sailors