Elizabeth Henrietta Campbell was born in Airds, Scotland in 1778 and as the wife of Lachlan Macquarie, became the first lady in the Colony from 1809 to 1821.

One of the duties of the governor’s wife was to create gentility and bring the refinements of civilisation to the colony. Elizabeth Macquarie was ideally suited to this rôle: “her clan heritage and family connections were impeccable and significant.” As one of the Scottish gentry she was educated with all the skills considered essential for entering polite society, including music and dancing.

Prior to their marriage and during their long engagement when Lachlan was in India, he wrote to Elizabeth desiring her to stay in London “in order to have the advantage of the best masters to improve her in Music, Drawing and French in all three of which elegant accomplishments, I am anxious she should excel.” However, Elizabeth must have felt fully proficient in these areas as she ignored Lachlan’s request and chose to live in Holsworthy, Devonshire.

In 1810 Lachlan became governor of NSW and as his consort, Elizabeth was at the heart of colonial society. An important aspect of this commission was the entertainment of officials and guests with balls, musical evenings, tea parties, dances and concerts. It is known the Macquaries brought a three-pedal Broadwood grand pianoforte with them, though details of performances are limited: “The grand piano she had brought with her was a great success…” and Thomas Hewitt of the 73rd Regiment accompanied Lady Macquarie on his clarinet, ‘in the best concerto music…in her fashionable and crowded drawing room’. It is assumed Elizabeth was equally accomplished on the piano and cello.

The history of Elizabeth Macquarie’s violoncello

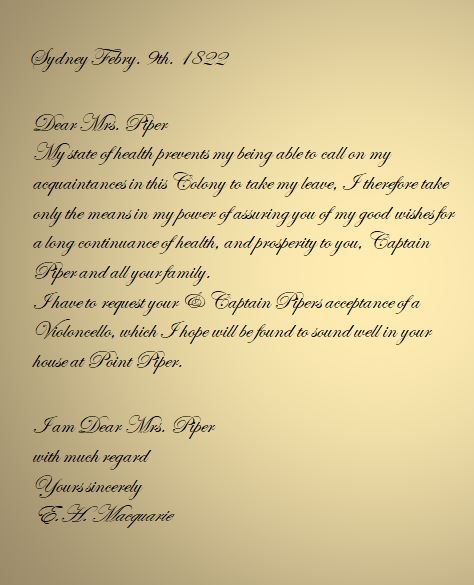

As Elizabeth prepared to leave to colony, she wrote to her dear friends John and Mary Piper, requesting them to take her violoncello, “hoping it would be found to sound well in your house at Point Piper.”

The Pipers were the leading socialites in the colony, and Captain John Piper had named his grand mansion Henrietta Villa in honour of Elizabeth Henrietta Macquarie. Their shared Scottish heritage must have been created a strong bond between the two families and they frequently meet at dinners, balls and dances where Scottish music was played

The cello and its wooden case appears to have been taken to Bathurst when the Pipers left Sydney and moved to Alloway House in 1827. Ownership of the violoncello appears to have subsequently passed through the Doyle/Prior family who had close associations with the Pipers. It was acquired at Sotheby’s auction (Melbourne) in December 1992 by the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales and. It is now held in the Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House.

A watercolour on ivory by Richard Read senior

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

The Flowers of Edinburgh

At the time the Macquaries arrived in the colony, ‘Scotch’ airs and dances were extremely fashionable, and were included on the dance programmes at Government House. One tune which may have been in the repertoire was The Flowers of Edinburgh. There are several theories regarding the title, the most appealing referring to the beautiful young ladies of the town. The tune remained popular in Australia until the early 20th century and is still a favourite amongst folk musicians.

The first reference to the dance is Johnson’s 200 Country Dances for 1750, after which it appears frequently in different versions until the present day. In Australia, it has a continuous history from the earliest days of colonisation; it is significant to note that it was recorded at a ball in 1855, at a time when such dances had completely disappeared from English dance programmes. During the early 1900s it was still being danced socially, prior to the establishment of the Royal Scottish Dance Society in Australia. Since the Society’s establishment it has no doubt been danced somewhere in Australia every week of the year.

This version of the dance is from Book 1 of the Royal Scottish Country Dance Society which gives The Ballroom, 1827 as its source.

The Flowers of Edinburgh

Flowers of Edinburgh mp3 Arr. Roland Clarke

Print music

Country dance: Triple minor longways.

| A1 | 1-6 | 1st lady casts off two places, [i.e. dances down behind 2nd and 3rd ladies], then crosses over and dances up behind 2nd and 3rd men to her partner’s original position. At the same time, 1st man follows his partner, crossing over and dancing behind 2nd and 3rd women, then up the middle to his partner’s original position. |

| 7-8 | 1st couple set to one another. | |

| A2 | 1-6 | Repeat the first 6 bars, but with the 1st man leading and the 1st lady following. Finish in original positions. |

| 7-8 | 1st couple set to one another. | |

| B1 | 1-8 | 1st couple lead down the middle and up again. |

| B2 | 1-8 | 1st and 2nd couples pousette. |

Elizabeth played a significant role in the social and architectural development of the colonial, helping in its transition from a penal colony to a free settlement. She took a kindly interest in the welfare of women convicts, and of the Indigenous people. Elizabeth is recognised in the naming of many Australian landmarks including Mrs Macquarie’s Chair, Elizabeth Street (Hobart and Sydney), Campbelltown, Elizabeth Bay, Appin, and Airds.

Sources

Campin, Jack, Embro, Embro. The hidden history of Edinburgh in its music. http://www.campin.me.uk/Embro/Webrelease/Embro/18misc/18misc.htm Accessed 14/3/2012

Cohen, Lysbeth. Elizabeth Macquarie: Her Life & Times. Wentworth Books, Sydney, 1979.

Ellis, M.H. Lachlan Macquarie. His life, adventures and times. Angus and Robertson, Sydney,1973.

Goold, Madeline. Mr. Langshaw’s Square Piano. The Story of the First Pianos and How They Caused a Cultural Revolution. Bluebridge, New York, 2008.

Keller, Kate Van Winkle & George A. Fogg. No Kissing Allowed in School. The Colonial Music Institute, Annapolis, 2006.

Museum of Sydney. Photograph and information regarding the cello.

Royal Scottish Country Dance Society. Book 1. Paterson’s Publications, London, 1985.

Sargent, Clem. The British Garrison in Australia 1788-1841: Bands of the Garrison Regiments. Sabretache ,Vol 40, issue 4. December 1999

Walsh, Robin. In Her Own Words. The writings of Elizabeth Macquarie. Macquarie University, Exisle Publishing, NSW, 2011

______________________________________________________________

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke.

Pingback: Australian Colonial Dance | Adventures in Biography

Pingback: Australian Colonial Dance – Michelle Scott Tucker