We spent the afternoon with the greatest pleasure & harmony being entertained with some beautiful songs by the ladies, after which the Governor having played on the violin, we had some minuets and country dances….[1]

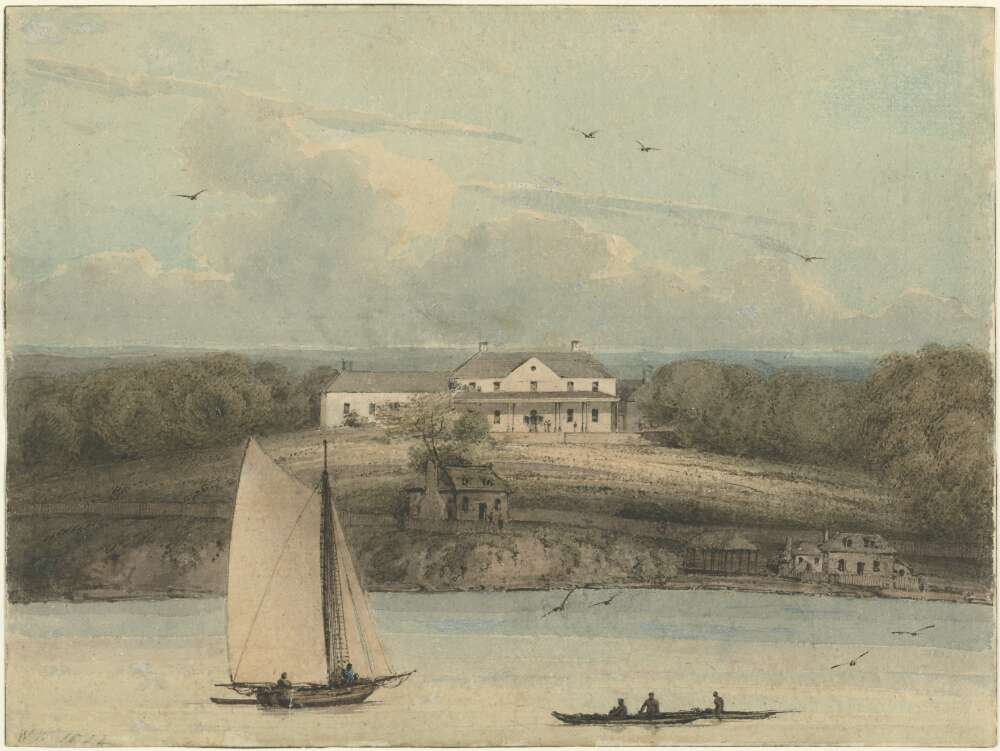

Government House, Sydney in 1802. William Westall.

National Library of Australia

On 18 January 1800, a select company gathered at Government House in Sydney to celebrate the anniversary of the First Fleet’s arrival at Botany Bay twelve years previously. This cheerful event was recorded by John Washington Price, a surgeon from the convict transport Minerva, who participated in the festivities.

This account is remarkable for the inclusion of small details – the ladies singing, the Governor playing, and the dancing of minuets and country dances. Never before had such an entertainment been described in the early colony and Price’s account provides a rare glimpse of social life in the fledgling settlement. The reference to the minuet demonstrates that an air of gentility was maintained even here in the remoteness at the end of the world.

The Minuet was considered to be the epitome of grace, elegance and stateliness. It developed in the French court of Louis XIV in the 1660s, before spreading throughout the Western world and enjoying great popularity for more than 150 years. A dance of the nobility, it was performed by one couple at a time, while the rest of the company watched. It was a symbol of precedence and power: danced first by the most important dignitaries and then by others in descending order of rank.

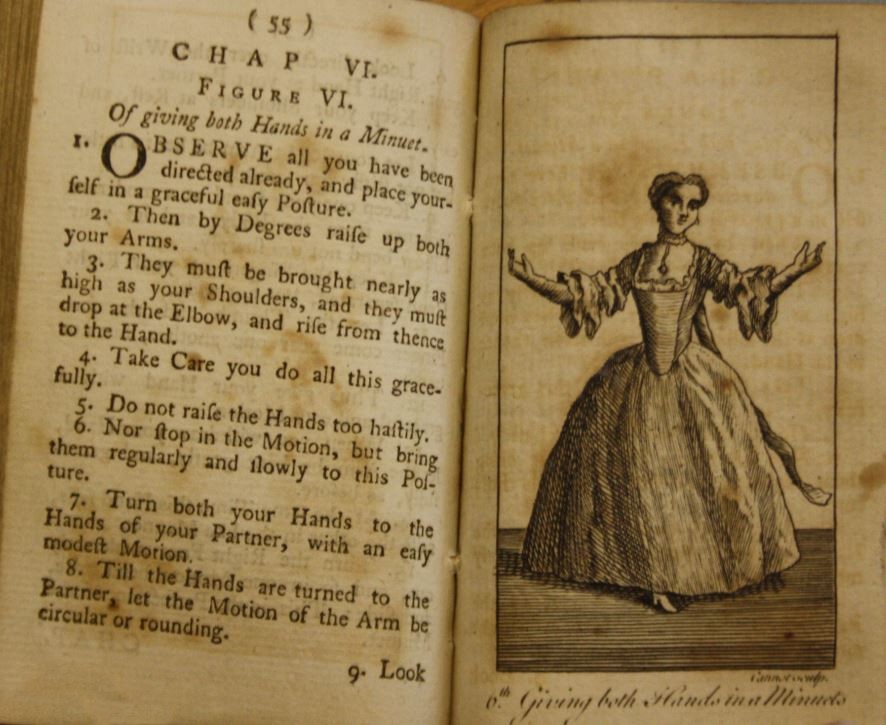

Instructions for giving both hands in a Minuet.

from The Polite Academy; or, School of Behaviour for Young Gentlemen and Ladies.

Intended as a Foundation for good Manners and polite Address. (1781) London

It was a dramatic and powerful dance that required considerable practise to perform well. It revolutionised dance technique by requiring the feet to be turned out (rather than naturally parallel) thus providing a more stable base and facilitating the sideways movements. The basic pattern of the dance consists of a core figure, a large Z floor pattern repeated through the dance, a right hand turn, a left hand turn and finally a turn in, which the man leads the lady with both hands. The minuet step is used throughout and a variety of additional steps may be employed for further ornamentation.

At Court and fashionable assemblies, all balls opened with minuets, followed later in the evening by the more socially inclusive country dances and reels. It became essential for all privileged children to be taught this dance as a prerequisite for entrance to polite society. The ability to dance well demonstrated a refined upbringing.

In the early days of the colony, those who considered themselves genteel strove to maintain their cultural and artistic traditions including, of course, proficiency in the minuet. Music for the 1800 dance at Government House was probably supplied by the band of the New South Wales Corps. On this occasion, this may have included King George III’s Minuet honouring the King, whom Hunter had meet upon his appointment as Governor. Other popular tunes at this time included Lord Howe’s Minuet, and Admiral Rodney’s Minuet (both patrons of Hunter) and Foote’s Minuet, which Elizabeth MacArthur had learned to play on the First Fleet piano.

Listen to King George III’s Minuet

Despite its reputation, the minuet was not only danced by the elite – there were convicts who knew how to dance a minuet, including François Girard.

Eliza Kent – The First Lady

Eliza Kent danced the very first minuet at Government House with Governor John Hunter. She was a well educated woman, married to Captain William Kent, nephew of Hunter. Eliza was regarded as “an intelligent, vivacious and devoted wife who was willing to accompany her husband on the long voyage to New South Wales.”[2]

When Hunter was appointed as the second Governor of New South Wales in 1793, he sought the support of his close relatives: William, who was promoted to commander of one of the ships to convey them to the colony, and Eliza, to fulfil the role of First Lady. Arthur Phillip, the first governor, had not graced the colony with an official consort; however, Hunter felt the settlement would benefit from the presence of a lady and invited Eliza to undertake the role normally occupied by the governor’s wife. Hunter first arrived in the colony as an officer on the First Fleet ship Sirius, and now, returning as Governor, hoped to establish a “polished civil society”.[3] As a bachelor, he required a lady to assume the official duties which were part of the elaborate web of functions and protocols at Government House.

A fashionable ballgown from 1799.

Eliza may have worn such a gown at the Government House celebration.

Bath Costume Museum.

“The Governor’s wife was both the emblem of British rule and an acknowledged social leader, a woman with a significant symbolic and actual role in the ordering of colonial society.” [4]

A small elite of civil, military and naval officials dominated the upper echelons of society and a gentleman’s standing was determined by the office he held. From the beginning Government House was at the centre of society and the governor was preeminent. Eliza was a key figure as the Governor’s designated consort – the First Lady in the colony.

Little person information is known about Eliza and no portrait exists, yet the records suggest she was an intelligent and clear-thinking individual. Upon her marriage to her cousin William Kent in November 1791, she wrote that “her ambition was … to retire with the Man of my Choice, far from the Gay, the Giddy, and the Vain”. [5]

Not only did she preside over Government House for six years, she also circumnavigated the world twice, and was the first English woman to visit New Caledonia. Her accounts of this visit and of the voyage from New South Wales to England, provide exceptional insights, rising “above the narrow range of expertise prescribed to women.” [6]

In both accounts she mentions music and dance — obviously important elements in her life. In January 1801, a year after the minuets at Government House, she describes dancing to fiddle and drum on board the Buffalo on the voyage to England. Of her visit to New Caledonia, Eliza writes about the initial contact with the local people:

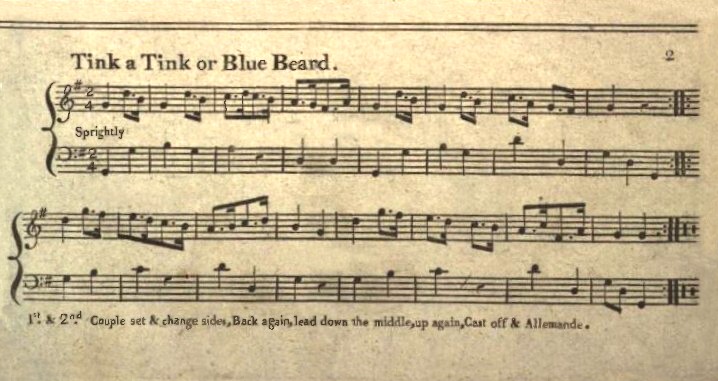

“We left nothing undone that we thought would please and amuse them. Some of our seamen danced under the orlop-deck to the sound of a violin, but the natives greatly preferred the flute, on which, to their great delight, Capt. K. and one of the officers performed several times. They listened attentively to the songs which a lady on board sang to that accompaniment, and joined chorus with her in the tune of “tink a tink.” [7]

It is most likely that Eliza was one of the ladies who entertained the company at Government House with some beautiful songs, as well as singing for the locals in New Caledonia. Tink a Tink was a very popular melody from the dramatic romance Blue Beard, or Female Curiosity by Michael Kelly, first performed at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1798. The tune also became hugely popular for dancing.

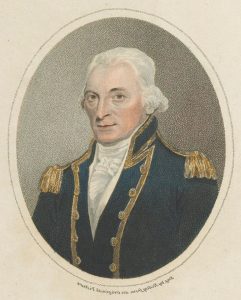

Governor Hunter

Captain John Hunter

Governor of New South Wales, 1801.

State Library of New South Wales

As a young man John Hunter wanted to pursue a life as a musician; however, his family insisted he follow a more traditional career in the Navy. He had a great aptitude for music and took lessons with Charles Burney, the man who would later become one of the world’s best known historians of music. Hunter benefited from his association with Burney, receiving a broad education and an introduction to the values of the Enlightenment. Described as “a gentle, humane and charitable” [8] man, Hunter maintained an interest in the arts throughout his life and was still playing the violin in his sixties, while Governor of New South Wales.

Hunter’s musical skill was useful on social occasions, and he may have found in music something of an escape from the cares of office. [9]

English country dances in Sydney 1800.

English country dances in Sydney 1800.

In 1800 the English country dance was the most popular form of social dance throughout Britain and its colonies, America and Europe. Large numbers of dances were published in annual collections in London, encouraging the fashionable to stay abreast of the latest trends. These were often linked to popular plays in the theatre; such was the case of Bluebeard.

Despite the time taken for a ship to arrive from Britain, the most up-to-date dances available for the Government House Ball in January 1800 would date from 1799. Collections published in this year included:

Bland & Weller’s Annual Collection of Twenty-Four Country Dances

Cahusac’s Twenty-four dances for 1799

Campbell’s 14th book of new and favorite country dances

Essex’s Sixteen New Reels and Country Dances

Hime’s Collection of Favorite Country Dances for the present Year 1799

Longman and Broderip’s Twenty-four dances for 1799

Platt’s Twelve new country dances for 1799 (book 4)

Preston’s Twenty four Country Dances for the Year 1799

Skillern’s Twenty-four dances for 1799

Thompson’s Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1799

When the lines of dancers assembled into sets for dancing, it was the role of the lady at the top of the line to select the dance: she might choose from a fashionable published collection, select an old favourite, or devise her own composition. She was required to be able to show the steps, the figures, and how they fitted the music. Eliza Kent may have chosen the new dance Tink a tink – there were several versions in the above collections – or she may have invented her own.

Music and dance instructions for Tink a Tink from the dramatic romance Blue Beard.

Hime’s Collection of Favorite Country Dances for the present Year 1799.

Listen to Tink a Tink.

Fashionable Ladies

All of Sydney’s elite was present at the ball as Eliza and her uncle entertained the “large and agreeable company, composed of the principal officers of the colony, civil and military, and the officers of Reliance, enlivened, graced & adorned with the presence of the most amiable ladies in the colony.” [10]

The ladies of Sydney must have been especially delighted to a have an opportunity to parade their newly acquired finery. A ship bringing the latest fashions from England had arrived at the most propitious of times:

“On the third day of this month [January 1800], the Swallow, East-India packet, anchored in the cove, on her voyage to China. In addition to … welcome news, she had on board a great variety of articles for sale, which were intended for the China market; but the master thought and actually found it worth his while to gratify the inhabitants, particularly the females, with a display of many elegant articles of dress from Bond Street, and other fashionable repositories of the metropolis. She remained here nearly three weeks, taking her departure for China on the 21st.” [11]

A ship arriving at Sydney Cove in 1800. Government House can be seen on the far left.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

In addition to imports of clothing, the gentlewomen of Sydney Town and Parramatta [12] had the opportunity to stay abreast of the latest trends with the aid of magazines. The late 18th century saw the publication of ladies’ magazines which included beautiful hand-coloured fashion plates to illustrate the current style of dress. In the first few years of the new century, the classical line held sway, completely influenced by the French revolution – “hair, heels, jewellery, cosmetics, petticoats and corsets- all were ruthlessly discarded in an endeavour to assume natural simplicity…” [13]

A fashion plate of ballgowns

July 1799

Lady’s Monthly Museum. p.70-2.

This fashion plate shows two examples of full evening dress from the Cabinet of Fashion, Ladies’ Monthly, July 1799 similar to those which may have been worn for the Government House ball.

Figure One: Muslin round dress, trimmed round the neck with lace; loose, full sleeves, with white or coloured band around the bottom; silver band around the waist. The hair drawn close up behind, and large curls or folds on the top, interwoven with a silver bandeau, with two large ostrich feathers. Necklace consisting of three rows of pearls, with a topaz. Shoes and gloves straw colour.

Figure Two: The same dress, of yellow muslin spotted with silver, with the sleeves drawn up on the arm.

High heels were abandoned; simple, elegant, low heeled shoes became the fashion. It was during this period that the heel-less ballet slipper was also developed. Typically, balls would continue until dawn. The introduction of more comfortable shoes must have been a blessing!

References

[1] Price, J. W., & Fulton, P. J. (2000). The Minerva journal of John Washington Price : a voyage from Cork, Ireland, to Sydney, New South Wales, 1798-1800. Victoria: The Miegunyah Press. [2] Groom, L. (2012). A steady hand : Governor Hunter & his First Fleet sketchbook. Canberra: National Library of Australia. p. 79 [3] Atkinson, A. (2004). Kent, Eliza. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Oxford University Press. [4] Clune, D., & Turner, K. (2009). The governors of New South Wales 1788-2010. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press. p.18 [5] Letter to William Kent, 23 Jan 1791, Mitchell L., NSW, Kent family papers, A3967 cited in Atkinson, A. (2004). Kent, Eliza. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Oxford University Press [6] Atkinson, A. (2004). Kent, Eliza. [7] Kent, E. (1808). Account of part of the South West side of New Caledonia : from a voyage performed in 1803 in the ship Buffalo from New South Wales. p. 337 [8] Australia’s heritage – the making of a nation : volume 1. (1988). Sydney: Lansdowne. [9] Groom, L. (2012). A steady hand . p. 97 [10] cited in Groom, L. (2012). A steady hand. p. 97 [11] Collins, D., King, P. G., Bass, G., Collins, M., Strahan, A., Turnbull, A., . . . Zaehnsdorf. (1804). An account of the English colony in New South Wales : from its first settlement in January 1788, to August 1801 (Vol. 2). London: Printed by A. Strahan … for T. Cadell and W. Davies …https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12668/12668-h/12668-h.htm [12] Fletcher, M. (1984). Costume in Australia, 1788-1901. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p.34 [13] Brooke, I. (1972). A history of English costume, written and illustrated by Iris Brooke. London: Methuen. p.113Acknowledgement of Country.

We acknowledge the traditional custodians of the Country on which we live and work, and pay respect to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge the impact colonialism has had on Aboriginal Country and Aboriginal peoples and that this impact continues to be felt today.

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke.

Pingback: The 3/8 Waltz | Australian Historical Dance