Irish Gentleman, Dancing Master, Australian Convict

Oh! to see him dance … you would go any distance or spend any time; it was delightful, sir – aye, I say delightful!

Lenihan, M. (1867). Reminiscences of a Journalist Limerick Reporter and Tipperary Vindicator.

Edward Elliot was a highly respected dancing master from Ireland whose life was turned around when he was accused of rebellion and sent as a convict to New South Wales.

Born on 2 October 1770 in Limerick, Ireland, Edward (Edmund) came from a well-connected family, his grandfather was a captain, and other relatives included a cavalry officer, lieutenants and captains. Edward became a talented dancing master and at the age of 35 married Mary O’Shaunnessy at St. Mary’s Cathedral, Church of Ireland, Limerick on 28th July, 1806.

As a Dancing Master, Edward travelled around a regular circuit of towns and villages where he taught dancing and held dances. There would be great excitement when the dancing master arrived as his visit was “a signal for universal fun and relaxation“ and ensured several weeks of music and dancing. Dancing masters were always treated with the greatest hospitality and might stay in one farmer’s house for the duration of their visit, or in a different house each night. His students learnt not only the steps and figures of the dance, but also a number of other useful skills: improving posture, grace and bearing, and good manners – how to invite a girl to dance, and how to politely accept. Many dancing masters provided their own music and carried a small fiddle so they could play as they demonstrated the steps. Students learnt the country dances, cotillions, and quadrilles popular at the time, while the most advanced dancers were also taught the solo dances that were highly esteemed for the skill required to dance them well. Dances now regarded as the basis of the tradition – St Patrick’s Day, The Blackbird, Three Sea Captains – were devised around this time, and perhaps Edward helped in their creation.

The first [best] dancer I ever met – he was the first in Munster, Leinster or Ulster, an inventor, sir, of dancing himself – his name was Edward Elliott (Ellard).

He was unequalled at the Moneen Jig. Oh! to see him dance it, you would go any distance or spend any time; it was delightful, sir – aye, I say delightful!

The Moneen Jig, you know, or ought to know, is the best dance that ever was known – a true, real, undoubted Irish dance; it would dazzle your eyes to see it danced, sir.

“The moment the scrape of the Dancing Master’s ‘kit’ of little fiddle was heard, all the cankering cares and blue devils…were supposed to vanish like the toads and snakes at the voice of St Patrick.”

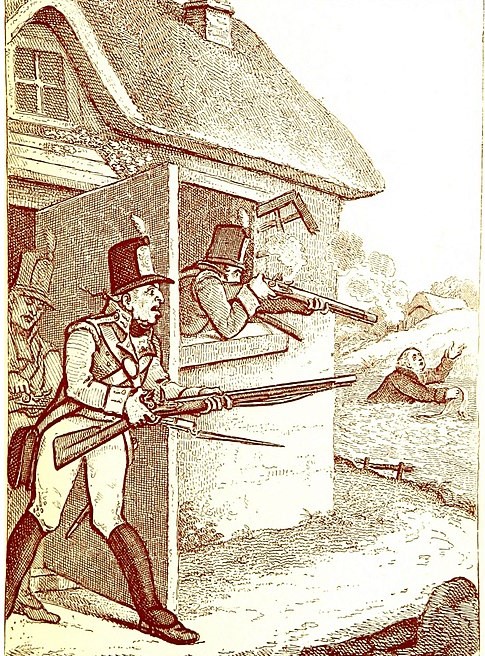

It was through the course of Edward’s work as he travelled from village to village that he was accused of spreading rebellion. It seems Edward was associated the Whiteboys, a secret Irish agrarian organization which took vigilante action to defend tenants’ land rights. In response to the wretched conditions placed upon tenant farmers and rural workers, the Whiteboys targetted landlords and tithe collectors in an attempt to punish their cruel oppression. The Whiteboys demanded absolute loyalty and developed a secret oath-bound society among the peasantry. In 1822, “An Act to suppress Insurrection and prevent Disturbance of the public Peace in Ireland” made it illegal for persons to take oaths for seditious purposes. At Edward’s trial, where others convicted of the same crime were sentenced to seven years, he was sentenced to life due to his occupation.

“The conviction of Elliott is important”, stressed the crown solicitor Matthew Barrington (later Sir), “as he was a travelling dancing master, swearing in Whiteboys in different parts of the country.”

Captain Rock: The Irish Agrarian Rebellion of 1821–1824.

James S. Donnelly, Jr. University of Wisconsin Press, 2009

Edward was convicted at Tralee, the County Kerry Assizes town, at the Spring Assizes, he was aged 51 years. Now incarcerated far from his family in Shanagolden, County Limerick, he must have feared for his wife and three children: his eldest son Alexander aged 15, his daughter Joanna 13, and Edward 9 years old. Would he ever see them again?

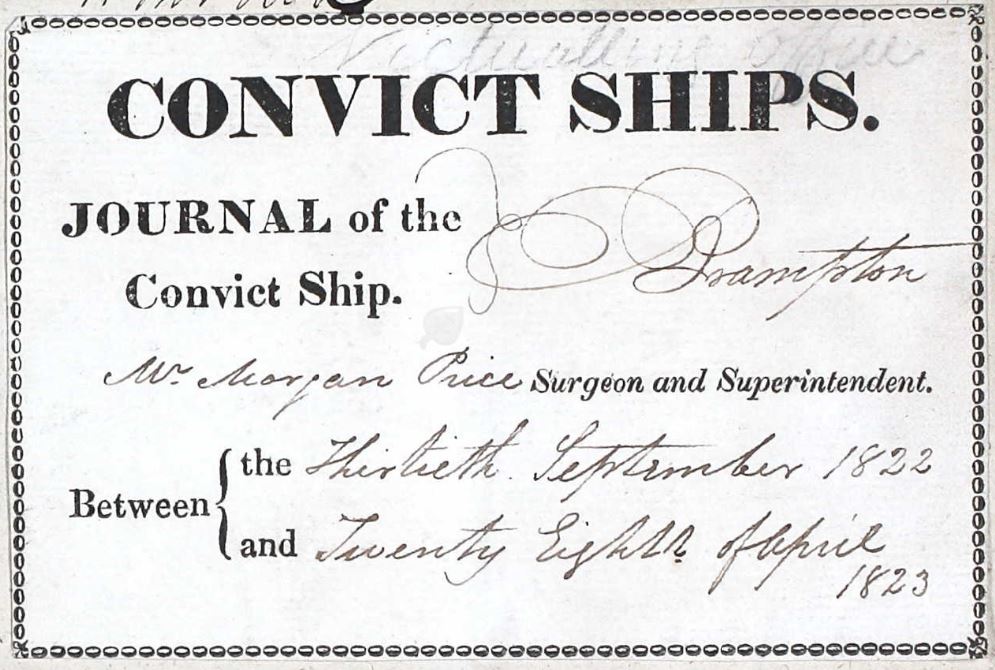

On 8 November 1822, Edward sailed from the Cove of Cork on board the convict ship Brampton Doctor Morgan Price, the surgeon superintendent in charge of the convicts, keep a medical journal detailing the incidents and daily regime throughout the voyage. Although the Captain, Samuel Moore was described as a violent and abusive man, the convicts seem to have been protected from his outbursts, unlike the military guards.

By this time convict ships were well regulated (thanks to the work of William Redfern) and Price writes about the hygiene measures taken to keep the convicts healthy; he also describes the education available to them during the voyage stating that “the greatest number of prisoners were very attentive to their schooling and several who came on board who were not able to spell or even had any knowledge of the alphabet were able to read with some facility.”

As was common practice, the convicts were encouraged to spend time on deck whenever the weather was favourable. Some surgeons actively encouraged dancing as a healthy activity, however, Price is silent in this regard mentioning neither exercise or recreation despite the fact that these diversions would have been part of the daily regime.

Brampton arrived in Port Jackson on 22 April 1823 and upon inspection Governor Brisbane proclaimed that he was pleased with the healthy appearance of the convicts. For Edward this was certainly not the case, as the surgeon had gone so far as to pronounce him ‘dead’ – an indication that his health was so poor that he appeared to be deceased. Perhaps due to his poor health or his age, Edward was issued with a Ticket of Exemption from Government Labour. His occupation was listed as Dancing Master, but there is no indication that he was permitted to follow this calling: he was first assigned in Airds (now Campbelltown), before returning to Sydney to work for G M Wade. Over the next year he was returned to the Hyde Park Barracks, sent to the treadmill for refusing his duty, and assigned to the shoemaker, Daniel McNutly (himself an ex-convict).

Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales

In 1826, Edward petitioned the Government for his wife and family to join him. This provision was available for convicts who had not committed offences in the colony and had enough income to support their families. This was generally only permitted for convicts with a Ticket of Leave and regular employment since the Crown would only cover the expense of the family’s travel with no further assistance once they arrived in the Colony.

Edward’s petition was approved, but unfortunately while he awaited the arrival of Mary and his children, he was charged with laziness and assigned to work, shackled in irons, on Road Gang 17, building the Parramatta Road from Missenden Road to Parramatta.

At the end of 1828, his dear wife and two of the children, Edward aged 13 years and Johanna aged 18 years, arrived in the Colony. The next year his eldest son Alexander arrived on board the Eliza II, and Edward’s life must have improved dramatically when he was assigned to his wife’s care.

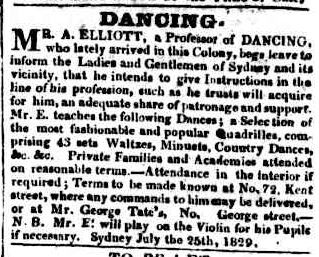

The is no record of Edward resuming his career as a Dancing Master in the Colony, however, for a time his son Alexander followed his calling. In 1829, The Sydney Gazette carried an advertisement, asserting Alexander’s considerable dancing prowess which had been passed on from his father and no doubt polished in Ireland as he anticipated his life in the new land.

A similar advertisement appeared in 1830, but after this time it seems Alexander and his brother Edward forged successful careers as publicans, owning many establishments in Sydney and the Illawarra – a more profitable lifestyle than dance teaching!

In 1831, Edward and Mary sanctified their union by marrying in their own faith at St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, Sydney – surely a great occasion for dancing! About this time the family moved to Wollongong which had become a favoured destination for former Irish Rebels.

For several more years Edward’s life continued to be shadowed by the government:

10 Sep 1833 Ticket of Leave No 33/615 granted.

Edmund Elliott, Dancing Master, He was 5′ 7″, dark brown hair to grey, hazel eyes with a cast in right. Crucifix 1801 E.E. on right arm.

Aged 68 years.

However, three years later in 1836, he was granted a conditional pardon.

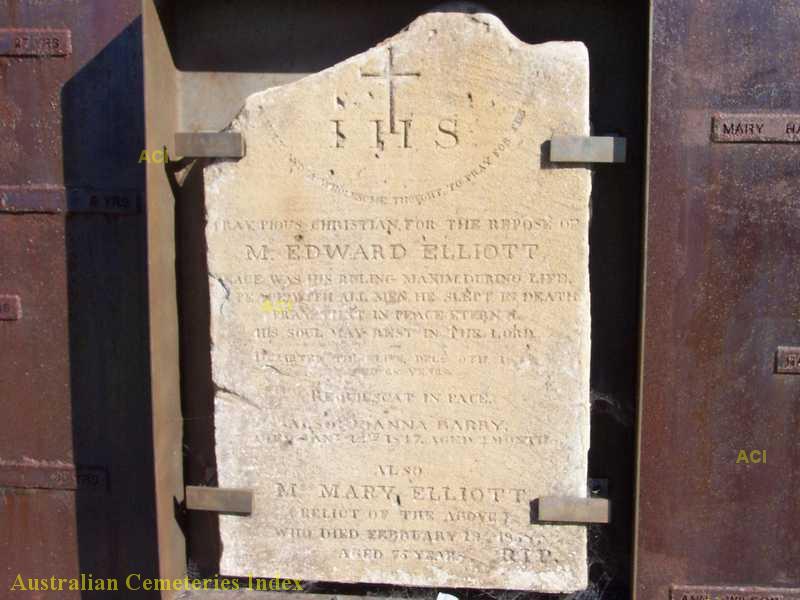

On 9th December Edward 1838 died in Wollongong, and his wife Mary nearly twenty years later on 16th February 1858.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to family historians, Joanne Flack and Reg Volk for providing information about Edward, his life, and family.