HMS Dolphin, under the command of the English explorer Samuel Wallis, arrived at the island of Tahiti in 1767, the first European ship to do so. Wallis had been sent by the British Admiralty to search for the Great Southern Continent in the Pacific. One of the indigenous inhabitants he met on the island was a young man named Mai. Two years later Captain Cook was greeted by the very same man, when HMS Endeavour reached Tahiti on its voyage to observe the Transit of Venus.

HMS Dolphin, under the command of the English explorer Samuel Wallis, arrived at the island of Tahiti in 1767, the first European ship to do so. Wallis had been sent by the British Admiralty to search for the Great Southern Continent in the Pacific. One of the indigenous inhabitants he met on the island was a young man named Mai. Two years later Captain Cook was greeted by the very same man, when HMS Endeavour reached Tahiti on its voyage to observe the Transit of Venus.

When Cook returned to Tahiti on his second voyage of exploration to the South Seas in 1773, he once again encountered Mai. Mai made the request to be taken to England where he believed he could request aid from King George III. He wanted to reclaim his ancestral lands on the island of Ra’iatea. These lands had been lost when the Bora Bora tribe invaded, killing Mai’s father and forcing the ten-year-old boy to flee to nearby Tahiti.

Cook was concerned about the ethics of taking the young South Sea islander to Europe, and only complied with the request reluctantly. Mai was taken on board the second ship in Cook’s expedition, HMS Adventure captained by Tobias Furneaux. On the voyage to England Mai worked alongside the crew who affectionately renamed him Jack.

They arrived in England in July 1774. The reception Mai received was enthusiastic: within three days, he was presented to King George and Queen Charlotte. During this audience he bowed appropriately, as instructed, before grasping the king’s hand and exclaiming, “How do, King Tosh!” – the closest pronunciation for ‘George’ he could manage. Their majesties were amazed by his poise and manners, for although Mai was a commoner, he presented himself as a noble chief.

Omai kneeling before King George III and Queen Charlotte. Courtesy of National Library of Australia.

With the approval of the king, the stage was set for Mai’s dazzling social life in England. His name became transformed to Omai due to a misunderstood translation (‘O Mai’ = ‘it is Ma’i). He quickly became a much-loved celebrity, and was proclaimed “the Lion of London”.(Matsuda, 2012). Joseph Banks was delighted to act as host for his Tahitian friend and introduced him to the elite of London society, including the influential supporter of Pacific exploration and First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich.

This was not the first time a South Sea islander had impressed European society. Five years previously the French voyager, Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, had created a similar sensation by introducing the Tahitian man, Ahu-toru to Parisian society (Aughton, 2004). The English were eager to welcome their own exotic visitor.

At the time, philosophers of the Enlightenment were obsessed with the concept of the “noble savage” – the notion that people remote from the inequalities and problems of European civilisation were closer to perfection and untainted by vice (Rigby & van der Merwe, 2002). Omai was expected to be the personification of this ideal, being free from corruption and displaying the innate goodness of humanity. Being naturally gracious, kind and inquisitive, Omai confirmed this perception. He was feted by London society with banquets, tea parties, visits to the House of Lords, theatre and the races. He learned to ride, dress and dance in the English mode, and received many gifts ranging from a medieval suit of armour to a barrel organ. His portrait was painted by a number of renowned artists including Joshua Reynolds and Nathaniel Dance.

After two years, Omai tired of life in England and longed to return to his island home. This became a significant factor in the planning of Cook’s third voyage.

Cook revealed a sensitive side of his own personality in his journal, reflecting his close relationship with Omai, who regarded him as a father:

I observed that Omai left London with a Mixture of regret and joy; in speaking of England and such persons as had honoured him [with] their protection and friendship he would be very low spirited and with difficulty refrain from tears; but turn the conversation to his Native country and his eyes would sparkle with joy. (Cook, Beaglehole, Edwards, & Hakluyt Society, 1999, p. 435)

Omai was settled on the island of Huaheine, close to his original home. Cook purchased land and built Omai a large English-style house with a stable for his two horses, a garden and orchard.

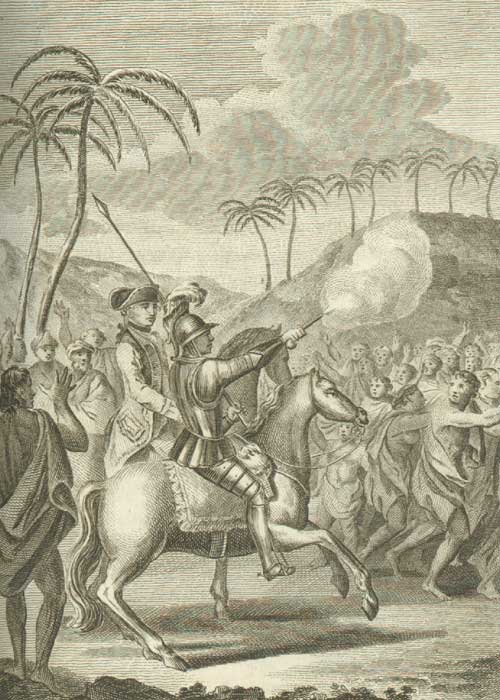

Omai returning to Tahiti, wearing armour and mounted on a horse. Courtesy of the Captain Cook Birthplace Museum.

Before continuing his voyage, Cook attempted to secure Omai’s future with a series of festivities, intending to impress the new neighbours with the esteem in which Omai was held.

These festivities included dinners and a concert with the ship’s band of flutes, violins, hautboys (oboes), bagpipes, trumpets, and drums. An island dance, a heiva, was arranged. Omai entertained by playing the hand organ he had received as a gift in England, and there were “entertainments for the young princesses and their brothers, with music and dancing according to the English fashion.”

During further celebrations held on board the HMS Resolution, it was noted that the “young ladies…could hardly refrain from dancing the whole time” when they heard the music, and were particularly delighted with the bagpipes. After the tables were cleared, the ladies joined the company, and then hornpipes and country-dances after the English manner commenced, in which the young joined with great good humour. Almost every other night there were displays of fireworks.

Finally the time arrived for parting and Omai threw his arms around Cook and burst into tears. In his journal, Cook fondly recorded :

His gratifull [sic] heart always retained the highest sence [sic] of the favours he received in England nor will he ever forget those who honoured him with their friendship and protection during his stay there.

Having been a celebrity in England, Omai found it difficult to return to island life and was not readily accepted by his neighbours. The local chiefs regarded Omai as a nonentity, but had nonetheless, been happy to accept his gifts and entertainments. During Captain Bligh’s visit in 1779, the locals reported that Omai had only lived two and a half years after Cook’s departure.

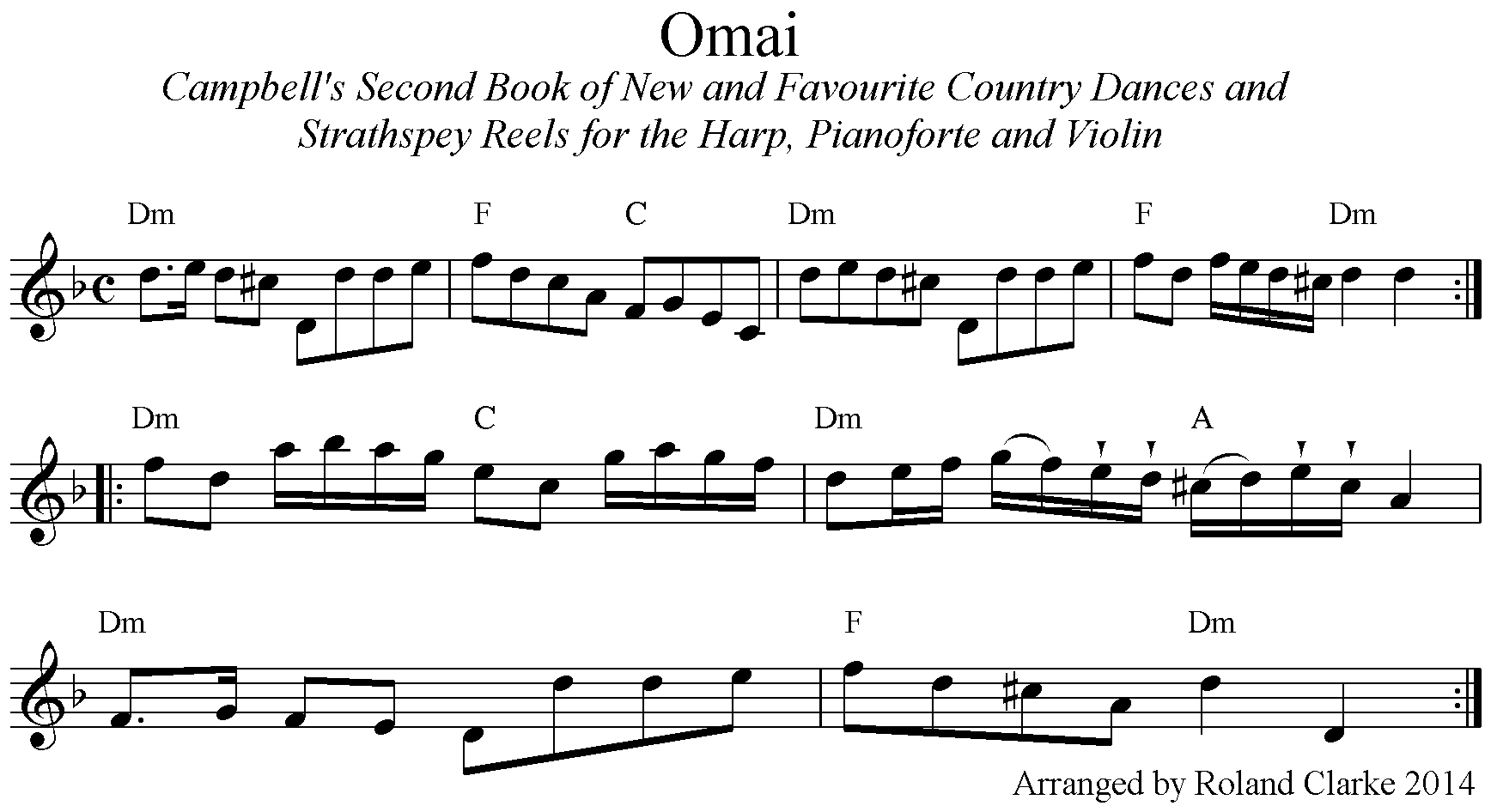

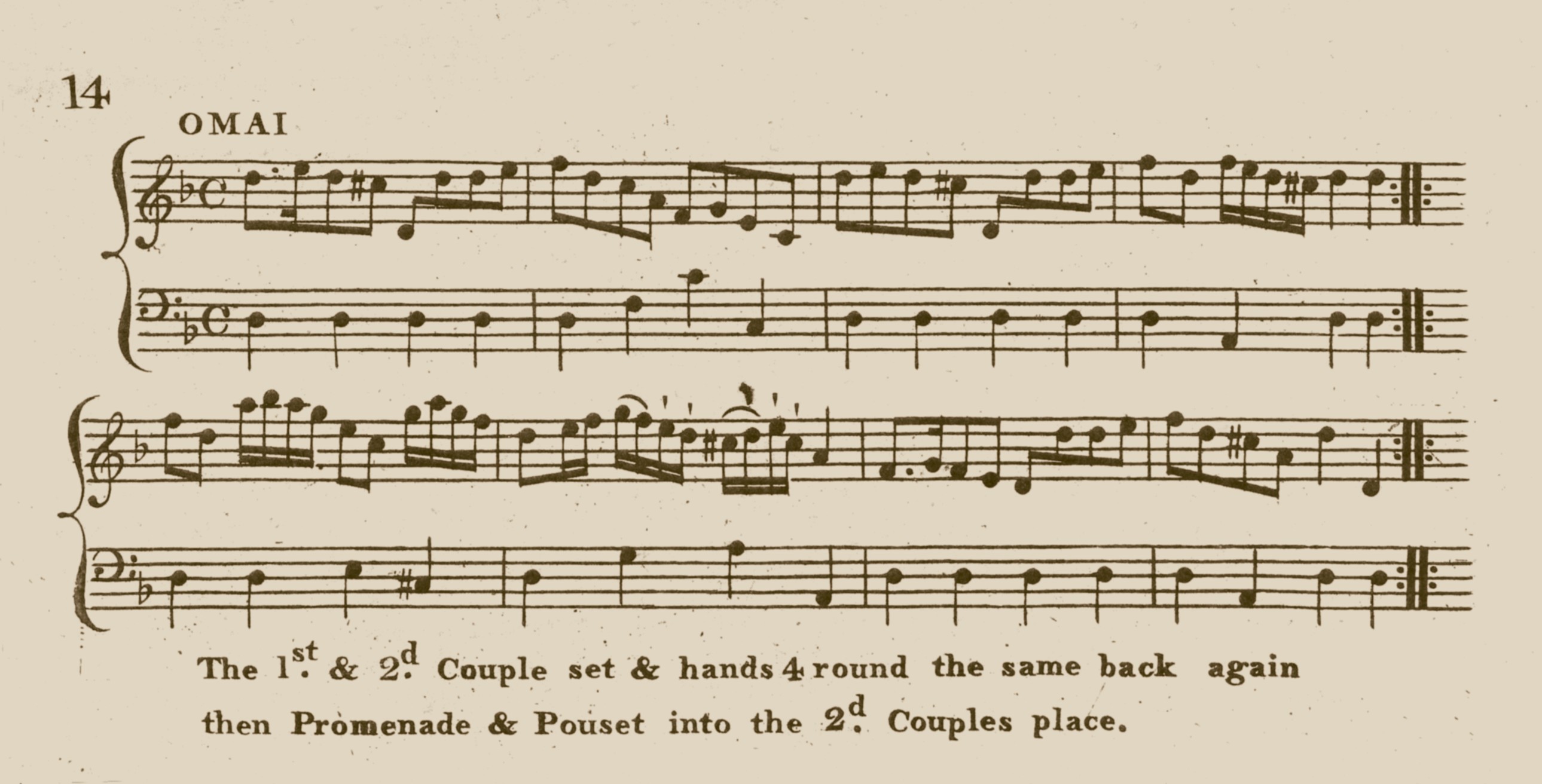

Omai inspired artists, writers, poets, and actors, and after he left England, his life was celebrated in the theatre with the highly successful stage production Omai or, With Captain Cook around the World (1785). This pantomime included many dances, and one entitled The Ruffians was published as the country dance, Omai in Campbell’s 2nd Book of New and Favourite Country Dances.

Music by Phillip’s Dog and The Whoots: Roland Clarke (violin), Isabel Clarke (whistle), Shira Kammen (violin), Jim Oakden (Guitar), Charlie Hancock (piano accordion).

Country dance: Three couple longways set.

| A1 | 1-4 | 1st and 2nd couples set twice to partners. |

| 5-8 | 1st and 2nd couples join hands and circle left. | |

| A1 | 1-4 | 1st and 2nd couples set twice to partners. |

| 5-8 | 1st and 2nd couples join hands and circle right. | |

| B1 | 1-8 | All three couples promenade anticlockwise, down the outside of the gentlemen’s line and back to place. |

| B2 | 1-8 | Poussette for three couples, first gentleman retiring to start, second and third gentlemen advancing. End in progressed positions, 2,3,1. |

Traditionally this was danced in a triple minor set, in which case the 1st couple dances a Poussette for two couples with the second couple 1½ times to end in 2nd place, and turn with two hands.

Music and dance instructions for Omai in Campbell’s 2nd Book of New and Favourite Country Dances and Strathspey Reels for the Harp, Pianoforte and Violin, c.1787. Courtesy ©CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collection: The Mitchell Library, Special Collections.

Select Bibliography

Aughton, P. (2004). Captain Cook’s second voyage of discovery. Great Britain: Pheonix Paperback.

Cook, J., Beaglehole, J. C. J. C., Edwards, P., & Hakluyt Society. (1999). The journals of Captain Cook. London, England ; New York, N.Y., USA: Penguin Books.

Hetherington, M. (2009). Discovering Cook’s Collections: UNSW Press.

Hetherington, M., & National Library of Australia. (2001). Cook & Omai : the cult of the South Seas. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Matsuda, M. K. (2012). Pacific worlds : a history of seas, peoples, and cultures. Cambridge, [Eng.] ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rigby, N., & van der Merwe, P. (2002). Captain Cook in the Pacific. Greenwich, London National Maritime Museum.

Salmond, A. (2003). The Trial of the Cannibal Dog. Captain Cook in the South Seas. London: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books.

Wills, K. L. (2018). Fancy, Spectacle, and the Materiality of the Romantic Imagination in Pacific Exploration Culture. UC Riverside.

______________________________________________________________

This resource was created on the lands of the Gubbi Gubbi people.

We pay our respects to their elders past and present.

Sovereignty was never ceded.

______________________________________________________________

Header credits:

1. Portrait of Captain Cook by Nathaniel Dance-Holland [Public domain]

2. A jig on board by Cruikshank. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

3. View of the South Seas by John Cleveley the Younger [Public domain]

______________________________________________________________

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke.