Background and history

In 1796, the Waltz music began to be used for country dances in the British Isles. Our collection* of music and dance manuscripts have nothing specifically called a waltz before this time before a sudden flurry of waltz dances and tunes began to be published starting from this year. The modern musician will be surprised to learn that these waltzes were almost exclusively in 3/8 time rather than the more modern 3/4 time.

The earliest 3/4 waltz in our collection is the Copenhagen Waltz in 1814, with only 18 further 3/4 waltzes being published over the following 10 years where our collection ends. Many of these have names evocative of Germanic Europe, such as The Emperor of Germany’s Waltz, The Strasburg Waltz and the Genoese Waltz. In some cases, such as Bown 1821[1] and Clementi 1821[2], 3/8 and 3/4 waltzes appear in the same book, and in Bown, on the same page. This implies a significant difference between the two time signatures rather than simple negligence or ignorance. I have been calling the two varieties English waltzes if they are in 3/8 time and German waltzes if they are in 3/4 time

With this in mind, the most likely interpretation is that a 3/8 waltz is much quicker than modern 3/4 waltzes tend to be. Using shorter note lengths is a good way of indicating this. However, there is also a significant competing dance form occupying the triple-time niche: the minuet.

The minuet, as a slow 3/4 dance, was still being played and danced at least as late as 1800, where two turn up in the sailor William Litten’s personal collection of music. Minuets were also danced at government house in 1800. While it was a style that was falling out of favour, its presence in a sailor’s collection implies that they were done regularly enough that a common fiddler would have a few favourite minuets and they were being done often enough to merit being written down. Quite simply, it would be surprising for a new, slow triple-time dance form to fill and displace an existing form, much as it would be surprising for a new dance or musical style to overtake another well-established form such as a jig or a hornpipe. A faster waltz, with a close embrace and twirls, was also more likely to encourage the scandal it triggered with its introduction.

It was probably not until the minuet began to die out more widely that the waltz slowed down. Without a slower dance style, the remaining 3/8 time dance would have slowed to 3/4 to fill the choreographical niche left behind. From our collection of manuscripts, it is unclear when this may have happened, but Alexander Laing’s 1863 manuscript still primarily uses 3/8 as its time signature for waltzes.

Differences between waltz styles

Both 3/8 and the older 3/4 waltzes are still somewhat different to the modern style of waltz. A modern waltz is characterised by being somewhat slower, with a distinctive swing. A good example of this is Margaret’s Waltz by Pat Shaw

Note how the pairs of quavers have a distinct swing to them, and the tempo is leisurely. Each beat feels quite distinct, and it suits that classic Om-Pa-Pa base rhythm, like so:

The 3/8 Waltz

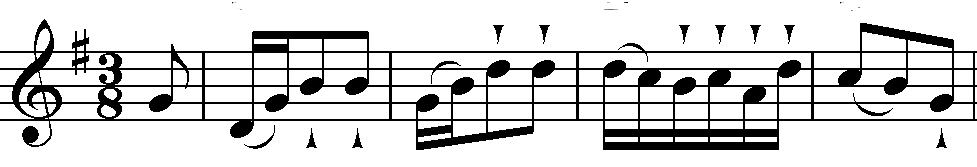

The 3/8 waltz has numerous features that stand out as distinct from the modern style. Firstly, it favours semiquaver runs, almost never having notes held as relatively as long as the minims of Margaret’s Waltz. Secondly, rather than having three distinct beats per bar, each subdivided into two, 3/8 waltzes have only the one strong beat, subdivided into three, in the same way that a 6/8 jig has two strong beats each subdivided into three. Thirdly, as a consequence of the first two, they feel faster. Slowing them down makes the dance crawl, and they often feel stilted as a result. Finally, as a consequence of the last point, they tend to be straight rather than swung. Swinging ultimately is about lingering on a beat for a little longer, so is not really possible when there’s only the one beat, and either makes the tune feel rushed or busy.

Taking all of these into consideration, here is an example: Lord Castlereagh’s Waltz

Here is the tune played as a 3/8 waltz

And here it is played in an exaggerated modern waltz style, to highlight the significance of the changes.

For accompanying instruments for chords etc., I favour a simple dotted crotchet rhythm or a very downbeat heavy rhythm to emphasise the one major beat per bar feel.

The 3/4 Waltz

3/4 waltzes were, based on our collections, unusual during the early days of the waltz. As a general trend, they tended to have a “reverse swing” feel to them, as for example, the Copenhagen Waltz

Aside from this distinct quirk, they suit the modern style quite well, although they still prefer to be played a little faster, owing to the kick the reverse swing adds to it. As an accompaniment, the classic OM-pa-pa rhythm works well, with emphasis on the downbeat but still paying attention to beats two and three of.

Minuets

More commonly during the days of the early colony, a tune in 3/4 is likely to be a minuet rather than a waltz. Minuets were often included in books teaching people how to play music, Foote’s Minuet being a notable example – Elizabeth Macarthur learnt to play this tune on the First Fleet’s piano. The minuet is distinct from the 3/4 waltz in that it has a strong downbeat of every odd-numbered bar, with a weaker downbeat on the other bars. This is to match the phrases of the associated steps of the dance, which comes in two-bar phrases. Like a 3/4 waltz, each beat is more distinct, but it lacks its laid-back swing. That is not to say that the dotted quaver – semiquaver pair is not common, it just is more precise. The tempo is also usually a little more subdued than a waltz. As an example, here is the Honourable Miss Lennox’s Minuet from Fishar’s Twelve new country dances, six new cotillons and twelve new minuets dating from 1775-1780:

This sounds like this:

Again, to contrast it to an exaggerated modern waltz sound, here it is played a different way:

As a rhythmic accompaniment, I focus on beats one and three of each six bar phrase, dropping down at beat four and building back up over beat five and six. This is done to mimic a basic minuet step, which has a small pause on beat two.

3/2 tunes

A final triple time signature found historically is 3/2. This time signature had fallen out of favour even before the early days of the colony and occurs very infrequently. While there is evidence to suggest that it still survived, notably Jeremiah Byrne playing Bobbing John in 1832[3], it seems unlikely that it remained in common use. As a more complex time signature that were not commonly played in this time period, without a simple, universal guideline on how to play them, they are beyond the scope on this article on waltzes.

Conclusion

We hope that this article helps with your appreciation of various triple time signatures. If it does, or if you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below.

Footnotes and references

*Our collection of dance and music manuscripts is assembled from collections in Cecil Sharp House, the British Library, Cambridge University, National Library of Scotland, and the National Library of Ireland, ranging from 1767 to 1824, comprising of over 4000 tunes and dances.

[1] Bown’s annual collection of popular country dances for the year 1821: Arranged for the violin, flute, &c. With proper figures to each dances as they are performed at all balls and assemblies. (1821). G. W. Bown.[2] Clementi and Co.’s twenty-four dances for the year 1821: With appropriate figures for the violin, german flute or oboe. (1821). Clementi and Co.

[3] Police Report. (1832, December 6). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), p. 3. Retrieved January 30, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2209764