The small farm cottage where Cook spent his earliest years had a thatched roof which frequently leaked, a dirt floor, and no sanitation. Locally known as a “biggin”, this was standard accommodation for agricultural workers in the 18th century.

James Cook was born on 27 October 1728 at Marton-in-Cleveland, Yorkshire. His father, also named James, came from Ednam in Scotland and had travelled south to find work as a farm labourer. He met and married Grace (nee Pace) who hailed from the nearby village of Thornaby.

The couple settled into a small, two-roomed, clay cottage on the farm estate of Mr Mewburn and there in the damp and dimly lit abode James was born. He was the second of eight children, four of whom did not survive childhood.

Farm labourers were amongst the poorest members of society and their children were expected to work as soon as they were able. At the age of five, James would already be helping his father with the stock, watering horses and running errands.

When James was eight, his father accepted the position of farm manager of Aireyholme Farm near the village of Great Ayton. This promotion enabled the Cook family to move into a larger and more comfortable home, and brought the young James to the attention of Lord of the Manor, the wealthy Thomas Skottowe. He clearly showed promise at an early age and Skottowe soon recognised his ability and intelligence.

After learning to read at the small village school, James’ education continued at the day-school in Great Ayton, where Mr.Skottow paid a penny a week for him to be instructed in writing and basic arithmetic. Skottow further assisted James in obtaining an apprenticeship with William Sanderson, a grocer in the fishing village of Staithes. This career, however, was found to be “very unsuitable to Cook’s disposition”.1 The lure of adventure and the south seas called to James and after only eight months he resolved to take up a seafaring life. He moved to nearby Whitby and found employment on the colliers plying the east coast of England.

Dancing in Yorkshire

Dancing was ingrained in the social life of even the poorest communities. The English were noted for their love of dance and most were proficient in country dances, and percussive step dances.

In the farming community where young James Cook grew up, harvests, weddings and other special events were celebrated with dancing. It was known as a way to escape from the cares of everyday life, a happy activity that could be enjoyed at any time. Even if they had no musical instruments, people could still sing or beat out a rhythm to accompany their dancing.

Music for rural festivities was provided by musicians from within the community or by itinerant players, who were paid a penny for each dance. Most people learnt to dance from family and friends, immersed in the local culture, and sometimes via lessons from travelling dancing masters. These dancing masters regularly visited rural areas and were paid a few pennies to teach both dances and steps, often holding a community dance at the end of their visit.

Over the course of the eighteenth century the English country dance became increasingly popular. As the dancing master, Kellom Tomlinson declared in 1735:

… it has become as it were, the darling diversion or favourite diversion of all ranks of people from the court to the cottage in their different manners of dancing.2

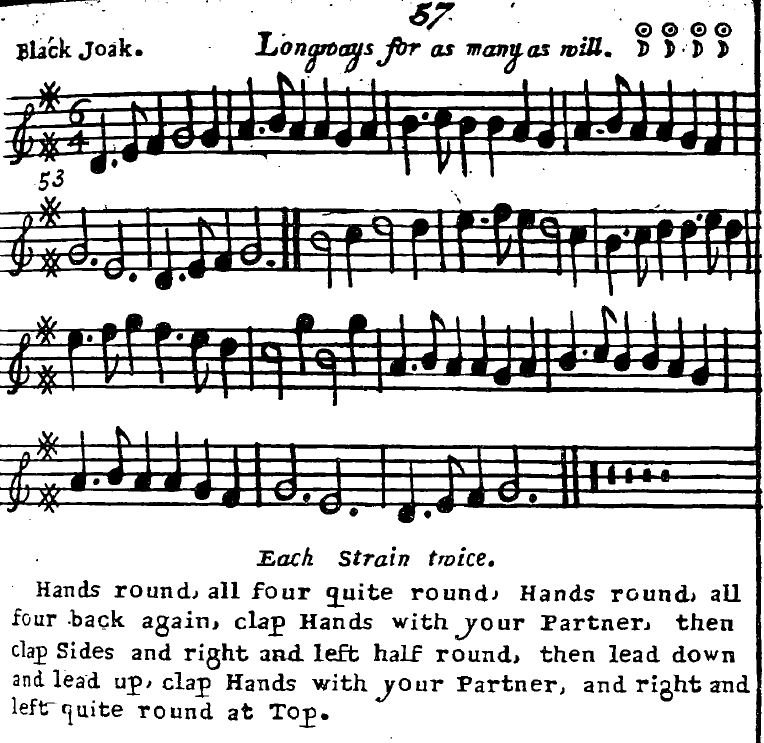

Country dancing was a favourite diversion in rural and urban areas, and also a cheerful part of shipboard life. Cook became a naval commander who was noted for encouraging dancing on his ships.3

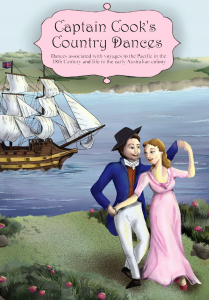

One dance current when James was a child was the Black Joak, which was published numerous times in John Walsh’s The Compleat Country Dancing-Master. This dance has endured and was collected as a folk dance in Goathland in the 1950s. Goathland is situated on the North Yorkshire Moors, just 9 miles from Whitby, the village where Cook began his nautical career.

Many English folk dances popular today have names reflecting a north country connection. This area also has a strong tradition of Long Sword, rapper, and clog dances. These dances may have been familiar to James as a child and young man.

______________________________________________________________

Sources

1 Kippis, Andrew. (1725-1795) A narrative of the voyages round the world performed by Captain James Cook : with an account of his life during the previous and intervening periods. https://archive.org/details/cihm_16842/page/n15

2 Tomlinson, K. (1735). The Art of Dancing. London.

3 Blasis, C. (1830). The code of Terpsichore (R. Barton, Trans.). London: E. Bull.

4 IMSLP Petrucci Music Library. https://imslp.org/wiki/File:PMLP90899-Walsh_Compleat_4th_ed_1740.pdf

Select Bibliography

Baskervill, C. R. (1965). The Elizabethan Jig and Related Song Drama.

Brockbank, Jonathan. (2012) Leisure: Rural Labourers: 1700-2000. Virtual Tours of York. https://sites.google.com/a/york.ac.uk/virtualculturetoursyork3/home/leisure-rural-labourers

Clegg, R., & Skeaping, L. (2015). Singing Simpkin and other Bawdy Jigs : Musical Comedy on the Shakespearean Stage: Scripts, Music and Context (1 ed.). Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Collingridge, V. (2003). Captain Cook Obsession and Betrayal in the New World. Great Britain: Ebury Press.

Dennant, P. (2013). The ‘barbarous old english jig’: The ‘black joke’ in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Folk Music Journal, 10(3), 298-318,427

Desmond, J. (1997). Meaning in motion: new cultural studies of dance. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Emmerson, G. S. (1972). A social history of Scottish dance: ane celestial recreatioun. Montreal;London;: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Mundle, R., & Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2013). Cook: from sailor to legend. Sydney, NSW: ABC Books.

Suthren, V. (2000). To Go Upon Discovery: James Cook and Canada, from 1758 to 1779. Toronto: Dundrun Press.

______________________________________________________________

This resource was created on the lands of the Gubbi Gubbi people.

We pay our respects to their elders past and present.

Sovereignty was never ceded.

______________________________________________________________

Header credits:

1. Portrait of Captain Cook by Nathaniel Dance-Holland [Public domain]

2. A jig on board by Cruikshank. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

3. View of the South Seas by John Cleveley the Younger [Public domain]

______________________________________________________________

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke.